The Ajax Dilemma is a fantastic interpretation of the Iliad by the classicist philosopher Paul Woodruff, centering on the tensions arising between Ajax, Odysseus, and King Agamemnon. The ethical lessons that can be drawn from this work are truly eye-opening. I here quote, paraphrase, and summarize some of the main themes of the book.

The Tragedy of Ajax

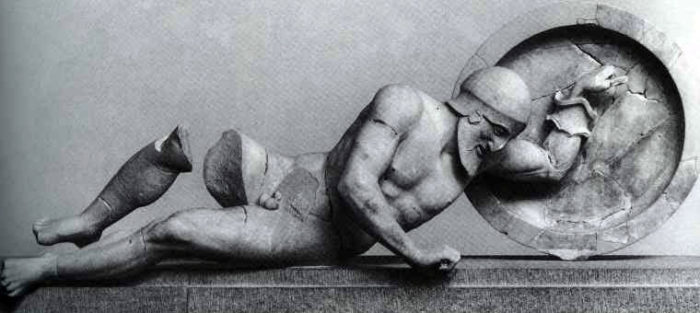

Ajax and Odysseus are two famous heroes of the Trojan War. Ajax is a towering leader with a colossal frame, strongest of all the Achaeans, a relentless warrior with great courage. Odysseus, on the other hand, is no great fighter, but he is a trusted counselor and adviser to the king. He is clever and highly ingenious, an eloquent speaker, renowned for his self-restraint and diplomatic skills.

Towards the end of the war, the great warrior Achilles is killed in battle. Who should get his highly prized armor?

As the man who now can be considered the greatest Greek warrior, Ajax feels he should be given Achilles’ armor. But Agamemnon awards it to Odysseus. Ajax is furious. He realizes that he has always been a dumb ox, easily controlled. He sees that for all these years of warfare he has been used – taken advantage of, by men he used to believe were his friends. His anger ultimately leads to his death.

According to Woodruff, Ajax is ignorant on one important point, however, and this ignorance fires his anger to the breaking point. Ajax does not understand the value of Odysseus’s contributions. He despises people who depend on the power of words, and he has contempt for anyone who would win a battle by stealth.

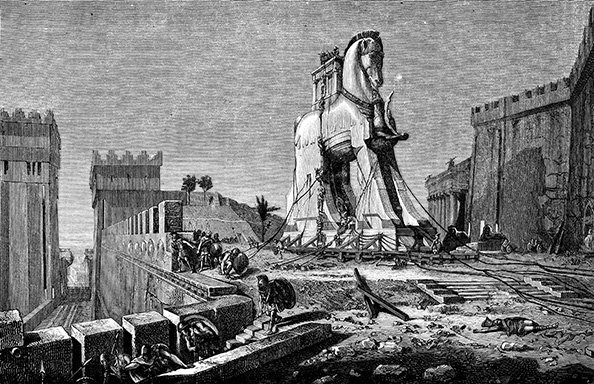

But Ajax is wrong. Troy will not be won on the battlefield. It will be won, improbably, by the Trojan horse, which only an Odysseus could imagine.

The author goes on to make another important point: whether or not Odysseus should have won, justice fails Ajax. Justice is not merely getting the right outcome. True justice must resolve a conflict in a way that leaves the community whole. Many believe that justice is not supposed to take people’s feelings into account, that it should simply deliver a verdict about what is right. But that cannot be correct. Justice is supposed to settle disputes, to bring us together in peaceful community. One cannot bring people together by ignoring their feelings.

Justice, for Woodruff, must be compatible with compassion. He sees fairness and justice as two very different concepts. Fairness is not wise. Fairness is following principles wherever they may lead, regardless of people’s feelings. Fairness is a trap in which justice and compassion die, where members of a team are hurt beyond repair. Yet fairness has often been thought to be the heart of justice. That cannot be correct. The heart of justice is wisdom.

Wisdom is a quality of leaders. It is not so mysterious as one may think, but it cannot be delivered by a formula. Being wise, a leader pays attention to others and sets an example for the people who report to him. The sort of action that is wise in one situation may be foolish in another. A wise leader may have a reason in mind that calls for action today and inaction tomorrow.

In this sense, there is no rule for solving the Ajax dilemma. If there were a rule for handling Ajax and Odysseus, the army would need no leadership. Algorithms require no leadership. Justice does. There can be no justice in a community without the good atmosphere that leadership can create.

On Leadership

Who gets a promotion or a raise? Who gets the corner office? Who gets the largest bonus at the end of the year?

Most competitions have at least one winner. You lost, but one of your colleagues won. Now you, as an insensitive loser, have one trump card to play: you can spoil the day for the winner. If you are sensitive, however, you will not do this. Joy in the workplace is too scarce a commodity to squander this way.

Wisdom is the ability to make good decisions in demanding circumstances. We have no tests to measure wisdom, because we have no criteria for good decisions. Yet what we want in leaders is not knowledge but wisdom. A wise leader can make use of other people’s knowledge, but managers who know so much they think they can act without wisdom are a menace.

If wisdom is an ideal, then so is leadership. Leadership is not the same as having power over other people. Power over other people can derive from many different sorts of things. The power of leadership grows from good qualities of a leader, such as wisdom, courage, justice, compassion, and reverence.

Management, on the other hand, can be defined as the knowledge or skill of getting people to carry out your wishes. Defined in this way, management is as good as your wishes. If you know what is best, your management skills will produce good results; if you are wrong, they can be disastrous. So management is not a really good thing. Management can be content with fairness, although that might well lead to a trap. But leadership aims at justice.

Management depends on some level of authority; leadership does not. Management aims at results that it can spell out and quantify; in doing this it sets a low bar. Under great leadership a group may do better than anyone can imagine. Good managers might try to be leaders, but leaders do not have to be managers, and may be better off not trying to be managers.

The mythical king Oedipus is called a tyrant for several reasons, but especially because he is terrified of losing his authority as ruler. Leaders are not afraid of losing their authority, because they don’t let themselves be ruled by fear. But it is also because they are confident they can do their jobs as followers. And because they don’t let their ambitions stand in the way of the goals they share with their followers. But there’s more to it even than that: a leader can still be a leader without authority.

According to Woodruff, leadership is not linked to hierarchical rank and authority. The most low-ranking members of a team can show tremendous leadership by setting example, sometimes even shaming higher-ranking people into doing what is best for all. Anyone, at any rank, who is not afraid to speak up, or who sets an example for others, shows leadership when others follow her. The only true leader in Melville’s Billy Budd is Billy himself, who has the lowest rank of any of the main characters.

This is something the military has known for ages: we can train people to be good leaders by training them to be good followers. Good followers have essentially the same skills and virtues as leaders. Good followers are not machine-like in the obedience to authority. Like leaders, they are focused on the common goal, and will help the leader see the way to get there. They are independent-minded.

Leaders are patient, and they take time to consider their options, when they have the luxury of doing so. Leaders recognize that their actions set examples for others to follow. So a leader has to expect her followers to think for themselves – even if that means talking back, or standing up to her. Leader are good learners.

Leadership is easiest to spot when it’s not there. Leadership is what Agamemnon does not have. He has authority: people obey him. And he has knowledge: he knows what tradition requires, and he thinks he knows what is right. But rank and knowledge do not make a leader.

To lead a team in a successful effort, one must appreciate the different contributions the team members make, and help them appreciate each other. It requires one to find ways to recognize exceptional work without insulting those who are merely good.

Throwing someone off a team is sometimes necessary. This is painful for both the leader and the team. But leadership should be able to bring a team through such an experience without loss of morale; indeed, morale will improve if the team recognizes that freeloaders will be dropped.

Above all, wisdom is knowing who you are. You are a human being: you will die someday, and before you die you have time to make mistakes, some of them serious. Human beings are vulnerable to error. The human situation is messy. People will not always respond to your actions as you would wish. The good decisions you make could lead to trouble, your reforms could set things back, your good deeds could be counted against you. That’s what it is to be a human in a human context.

Living with wisdom involves attitudes and emotions, and these affect your actions. It opens you up to the advice of others, forces you to look critically at yourself, and prepares you for things to go wrong. If you are humanly wise, you know that, despite your best efforts, you may fail, and the failure may well be your fault.

You must use the best judgment you can, as a leader, but you must remember that the best judgment can turn out to have been wrong. Leaders have often exercised good judgment when their judgments turned out to be false. We should evaluate a judgment not on the basis of the facts as they come to be known, but on the basis of the evidence available at the time the judgment was made.

Good judgment can easily be wrong. Yet all we have to go on is judgment, and the better your judgment is, the better for you and those who follow you. There is no recipe for good judgment. It can only be cultivated, by developing good qualities of character.

On Loss and Anger

Confucians try to cultivate calmness that is immune to anger, holding it to be an emotion that clouds the mind; Buddhists avoid anger in the belief that it binds us to the things of this world, thereby trapping us in the cycle of birth and death and rebirth. In the European tradition, Stoics held that anger expresses a rebellion against the Reason that guides the world, and so they too tried to learn to live without anger. But the God of Abraham can be angry, and so can Jesus; Jews and Christians are not Stoics about anger.

An important lesson that can be drawn from the story of Ajax is that anger can in fact be a good thing. Without it, Ajax would be a doormat. He is far too loyal and long-suffering. He has given more and risked more than any other soldier, day after day, without any special recognition or reward.

However, Ajax is a bad loser, but not because he snaps in the end; he is a bad loser because he has been losing all along and has not done anything about it. Instead, he has been accepting his losses quietly, so that no one knows his potential for anger. The commanders continue to take advantage of him, with no awareness of the dangers that lie ahead. A wise commander would have foreseen Ajax’s anger years before the surge; but in this army’s command, no one is wise.

Good losers know when to be angry. Anger can be too quick and too fierce. Good losers are angry enough, and no more. An individual is just insofar as his or her anger is keyed to injustice. If you tend to be too angry, or not angry enough, your sense of justice is out of whack.

Good leaders, because they are not tyrants, do not always get their way. They listen to others, and they may be persuaded to give up a cherished plan. They lose well, because, as leaders, they are not out to win anything for themselves personally. Leaders need to have followers who know how to be good losers, and for that they need to set good examples by losing well.

Many losers are self-deceived. They feel that they must have been stabbed in the back by some secret enemy. They know who the enemy is, and in their hearts they harbor a passion for revenge.

Some losers are winners but do not realize it. Their egos are so tender that they take the slightest setbacks as major losses. Tender egos are not deceived about the quality of their work, but they are wrong about what are entitled to on the basis of that work. Good winners know they should not win all the time.

Leaders know when to lose gracefully, when to give others credit, and when to make use of talents of others that they do not have. They know when to be angry and when to be calm. Leaders are good losers.

On Justice

Justice must give Ajax his due, and Ajax is not perfectly rational. He cares too much about honor to be perfectly rational. If justice is to give Ajax his due, it must give the non-rational what is due to it. Justice must pay attention to the factors that govern human behavior, whether they are rational or not. That is Plato’s great insight. The main non-rational factors that drive human behavior fall in two groups: those to do with big emotions, and those to do with desires.

The goal of justice is pragmatic. Justice as a virtue of individuals and communities prevents civil war. When a society fractures from within, we know that justice has failed. We can know with some certainty how we could fail at justice, but we cannot know for sure – and therefore we must continue to discuss and debate – what would make our society more just. A philosopher would say that we can identify necessary conditions for justice without making progress on sufficient conditions.

Justice has to take the non-rational into account in order to be credible. However well people are educated, they are subject to passions. Especially disruptive of community are the non-rational passions that arise from people’s love of honor and fear of shame.

There is no simple algorithm for sustaining justice – no straightforward way to measure what is due to any particular member. Each human being is different from every other, and each makes a unique contribution to the whole.

Someone must make hard decisions. Many people will dislike the decisions, but someone – ideally the one who made them – must have the ability to convince people that the decisions are a fair approximation of justice. A leader decides well, communicates well, and is trusted. A just society needs leaders.

If Ajax and Odysseus were doing the same kind of work, and contributing the same kind of value to the joint effort of the army, we could appeal to a simple principle: equal rewards for equal work. But the Ajax dilemma is not so easily solved because the two contestants work along different scales of value.

So it is with Odysseus’s children in our time: the finance whiz who dreams up more profitable derivatives – our banks must pay him enough to keep him away from rival banks; while the academic children of Ajax – the heroic teachers who manage heavy loads without tenure – are paid at roughly the rate of lawn-care workers.

Labor markets results are not (or not merely) an expression of power; they express the values of the society that creates the markets. If early childhood teachers are paid less than college professors, this represents two facts: more people can qualify for one job than the other, and society sets a higher value on one job than the other. The market does not give people what we believe is due to them.

The two soldiers’ contributions are incommensurate because they represent competing values, and no procedure can resolve the competition by itself in a way that sustains community. If justice can be found in this area, then, it will not be based on procedures.

A clash of values cannot be resolved solely by appeal to a fair procedure – unless, that is, we assume a high level of rationality on the part of Ajax and Odysseus. The trouble with fairness is that it wants to treat everyone the same, or as nearly the same as possible. But justice – if it is to serve its primary purpose of resolving disputes amicably – must pay attention to individual differences.

Goodwill is essential. No judgment, however good, will resolve disputes unless the people involved have justice in their souls – the qualities of soul that help them accept a wise settlement. Justice works without principles, but it cannot work in a moral vacuum. The society and its members must share certain virtues. And through sharing virtues they must be capable of working out a rough consensus on how to give the members their due. The virtues that support a just society must exist both in soul of the individual and in the culture of the community.

Wise leaders serve a number of purposes in justice. Their skills in communication, along with their personal credibility, will help make the community’s decisions credible. And by their personal qualities they will set good examples that help sustain a culture of justice. Leadership is a matter of ethics; where it occurs, it moves people not by force or fear but by the virtues of the leaders. The virtues of leadership start with justice and compassion but include also courage and wisdom. No one can give a recipe for growing any of these virtues.

Plato’s theory of justice is built around a pragmatic goal: the cohesion of a community that allows for human irrationality to work alongside reason for the common good. Such an approach is not complete without a conception of the good for human beings – what the ancient Greeks would call eudaimonia, “flourishing.” The goal of justice would be the flourishing of the community through the flourishing of each of its members. An individual flourishes when his or her capacities are well developed and put to good use.