Contemporary society literally surrounds us with a semantic mess when it comes to the way human interactions are to be “managed.” On the one hand, we are bombarded with terms such as collaboration, cooperation, and teamwork, usually on the grounds that they are ideals to be pursued; on the other hand, there is competition, confrontation, and conflict, which are associated with all kinds of unwanted behavior. How do we differentiate all these terms from each other? Do they really allow us to better understand the way we interact? How do we evaluate whether one or the other is in fact good or bad?

Words, words, words.

I will focus on two central concepts, namely competition and cooperation. Choosing to write of “cooperation” instead of “collaboration,” or “competition” rather than “rivalry,” may appear somewhat arbitrary. Ultimately, what matters isn’t really what terms we use, but rather what they refer to. Hang on to your philosophical hat.

Terms such as competition and cooperation are social constructs. The very idea of something being “competition” or “cooperation” presupposes a shared understanding of what counts as competition and cooperation. But experience shows that there are many different interpretations as to what exactly competition and cooperation are.

For instance, some define competition with respect to markets and an equilibrium of self-interested individuals, while others define it as something related to individual rivalry. The same kind of conceptual divergences can be observed for “cooperation.”

It is my belief that in order to use a word to successfully refer to a phenomenon, one does not necessarily need to know about a uniquely identifying description of that phenomenon; all that is necessary is that the use of the word be caused by some event that makes us name the phenomenon in question. Such a causal theory of reference allows for an explanation of how different people can refer to the same entity despite fundamentally different beliefs about this entity; it also implies that a word’s meaning evolves over time and can only be understood in historical context.

Hence the focus of this essay is not about words and definitions, but rather about the beliefs surrounding these words, as well as the things that the words are actually held to refer to. On the one hand, the concepts of competition and cooperation are social constructs, the existence of which depends on the shared beliefs of individuals. On the other hand, they also refer to real interactions that happen in a physical world. It is the link between these “shared imaginations” and “real interactions” that I wish to examine.

The next two parts of this essay will expose, and critically engage, the most common interpretations surrounding competition and cooperation. The list of definitions and mechanisms elaborated in these subsequent parts is not exhaustive and does not aspire to be so. However, they may provide a further step toward a clear and useful portrait of the way we think about the most fundamental aspects of human interaction.

Competition, the economist’s fetish

In the photo above, members of two opposing teams, the Up’ards and Down’ards, grapple for the ball during the historic annual medieval football game in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, United Kingdom. The two teams are determined by which side of the River Henmore players are born: Up’ards are from north of the river; Down’ards, the south shore.

In this game, players score goals by tapping the ball three times on millstones set into pillars three miles apart. There are very few rules apart from a historic stipulation that players may not murder their opponents, and the more contemporary requirement that the ball must not be transported in bags, rucksacks, or motorized vehicles. This provides an interesting example of a kind of “competition” that economists rarely address. So what is competition?

Two broad definitions of competition pervade economic and managerial literature: competition as a process of rivalry and competition as an end-state (or equilibrium) of rivalry between interacting agents. The first can be traced back to classical economists such as Adam Smith, who understood competition as a property of a relationship between economic actors. Smith’s notion of competition has been described as “rivalry in race – a race to get limited supplies or get rid of excess supplies.” This definition, which envisions competition in terms of individual rivalry, is often considered as being closer to common sense.

A second theoretical development of competition began to emerge with the advent of marginalism and perfect competition theory in the mid-nineteenth century. This conception has since endured to become part of neoclassical economic theory. Competition in the neoclassical sense is often understood as a “state” or “situation.” While classical economists such as Smith saw competition as a particular characteristic of the interaction between actors, neoclassical economists would define competition as a static property attributed to an aggregation of individual actors. A market is termed “competitive” when no single actor has the power to significantly influence the demand or supply of a good to his own advantage.

According to this view, competition is accordingly seen as the opposite of collusion and monopoly, terms which neoclassical economists generally do not clearly differentiate from cooperation. This stands in contrast to many earlier economists such as Smith, for whom “neither competition nor monopoly was a matter of the number of sellers in a market; monopoly did not mean a single seller but a situation of less than perfect factor mobility and hence inelastic supply; and the opposite of competition, was not monopoly, but co-operation.”

A relevant question for strategic management concerns the normative evaluation of competition, that is to say how one may answer the question: “is competition a good thing?”

Proponents of the end-state definition often see competition as an inherent characteristic of markets. But markets, it should be noted, are only able to function properly thanks to an amalgam of institutions. They cannot properly scale without (1) the recognition and respect of private property, (2) the proper enforcement of contracts, and (3) free and consensual exchange. An economic system cannot be called a market unless people follow these rules of the game. It is only because these rules are being followed that a competitive equilibrium emerges as self-interested individuals seek to satisfy their preferences.

According to mainstream economists, a state of unhampered or “perfect” market competition is, ceteris paribus, a state of Pareto efficiency, where no individual can be made better off without making someone else worse off. Insofar as Pareto efficiency is good, so is competition. Perfect competition is thus valued because it is seen as the only possible state in which resources are allocated efficiently.

However, both theory and empirical data now indicate that when the ideal conditions for perfect competition cannot be realized, the best way to increase economic efficiency is not necessarily to bring the market “as close as possible” to a state of perfect competition. The economists Lipsey and Lancaster (1956) have even theoretically demonstrated that in cases where several imperfections exist, fixing a single specific market imperfection will not necessarily increase the efficiency of the system.

This suggests that it is preferable to evaluate the different factors that affect the process of competition, and examine whether they can lead to positive social consequences in their specific empirical context. Determining if a given form of competition delivers a positive outcome requires, first, that we pay closer attention to the particular details of the process in which agents are engaged, and second, that we establish what a “positive” outcome is; in other words, that we clearly differentiate and justify both the means and ends of the competitive practice.

Unlike end-state competition, competition as a process is not limited to markets; many social practices, such as the Royal Shrovetide Football match, also count as “competition” despite the fact that they are not necessarily based on any formal economic exchange. To say that agents are “competing” means that they are vying for a desired resource which cannot be divided; in other words, they are engaged in an interaction which produces winners and losers. The fact that some will –or may– have a more beneficial outcome than others creates an incentive for agents to continuously invest efforts in their attempt to obtain this exclusive outcome.

The benefits of competition have nothing to do with its intrinsic merits; they are to be found in the fact that competition forces agents into a constant escalation of effort. Carefully designed competitive processes can thereby produce collective benefits which outweigh the losses of losers, creating “positive system effects”.

The virtues of competition are thus to be found in the rules that structure the competitive practice and their capacity to properly constrain the actions of players. Both the way we consciously design the institutions that constrain individual behaviour, and the ability of individuals to respect these rules, are potentially subject to normative evaluation – that is, on whether individual behaviour matches collective expectations.

The process of competition can be considered collectively beneficial “when players exercise restraint in the strategies that they employ, when they confine their adversarial behavior to certain specific contexts, and when they refrain from allowing moral lapses on the part of other competitors to transform the entire contest into a race to the bottom”.

While it may have its benefits and drawbacks, competition is perhaps best understood when defined in opposition to cooperation. The next section sheds some light on the ways cooperation has been conceptualized.

Cooperation, or how to have a good time together

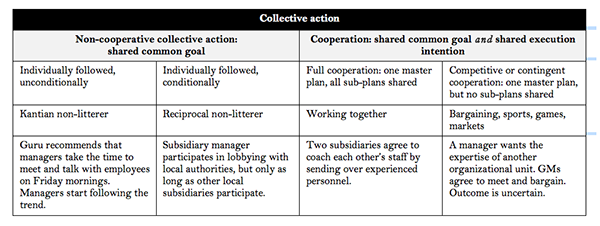

It is often assumed that sharing a common goal is sufficient for an interaction to be categorized as cooperation. Yet some have recently argued in favour of a clearer distinction between “collective action” and “cooperation”. The former implies that agents share a common goal, while the latter implies that agents share a common goal and share a coordinated execution intention (which is equivalent to saying that they depend on each other to achieve their common goal.)

What distinguishes cooperative from non-cooperative collective action are thus the shared/non-shared intentions regarding the execution of a common goal, as illustrated in the table below.

Behavioral economics has shown that people often choose to cooperate even when they can better serve their interests by acting selfishly. The motivation for cooperation thus seems to depend on context, and is not always strictly rational and egotistical. Some authors have delineated outcome-dependent drivers such as self-interest (“I-goals”) and communal interest (“we-goals”); others also speak of intrinsic altruism and coercive social norms.

Although interesting, theories on the drivers of human cooperation have for a long time remained embroiled in a nature-versus-nurture debate. Yet one thing is certain: whether it is intrinsic altruism or socially acquired attitudes (trust, openness, a sense of belonging, and so on), some kind of individual property seems necessary for cooperation to happen at a larger collective level.

Whatever the origins of cooperation are, there are no doubts that it can lead to positive consequences. The philosopher Joseph Heath (2006: 313) convincingly makes the case that cooperation exists to create mutual benefits, and that the primary purpose of social institutions is to secure cooperation, arguing that

if individuals simply seek to satisfy their own preferences in a narrowly instrumental fashion, they will find themselves embroiled in collective action problems: interactions with an outcome that is worse for everyone involved than some other possible outcome. Thus they have a reason to accept some form of constraint over their conduct, in order to achieve this superior, but out-of-equilibrium outcome.

The author contends that there are five types of mechanisms which allow such beneficial outcomes to be realized. These are: (a) economies of scale; (b) gains from trade; (c) risk pooling; (d) self-binding; and (e) information transmission.

Economies of scale arise from the fact that individual labor does not simply “add up” to an organizational activity; some tasks are such that adding another agent generates a disproportionate increase in output. If one individual is able to produce an output of x per unit of labor, an economy of scale is present when adding a comparable unit of labor from another individual increases output by more than x.

Gains from trade arise from situations where individuals may be able to achieve benefits by rearranging the distribution of goods, or tasks, among themselves. An appropriate redistribution is thus achieved through a process of exchange. This is exactly what allows a division of labor to occur. Particularly skilled individuals may agree to carry out their skilled tasks “for everyone,” while instituting a structure of reciprocity such that their other needs are taken care of by others.

Risk pooling is yet another strictly cooperative process which enables risk-averse managers to deal with uncertainty regarding the possibility of outcomes which they would be unable to deal with on an individual basis. Pooling resources to insure each individual thus increases everyone’s utility.

Self-binding is a mechanism allowing an individual to enlist others to help maintain his self-control. The mechanism allows individuals to deal with their irrational tendencies. An individual who authorizes others to punish him can guard himself against his own preference reversals.

Finally, information transmission allows individuals to economize on learning costs. Learning can sometimes be achieved without any form of cooperation, through observation and imitation, for example. However, most knowledge is transmitted through a process of interactive learning which requires cooperation. Hence most of what we know is not a result of individual experience, but is acquired through our communication and cooperation with other individuals.

In sum, neither competition nor cooperation refers to a clear-cut causal mechanism; these concepts rather refer to categories of interactions, which may involve different causes, processes and outcomes. What competition and cooperation are taken to be varies considerably depending on the social phenomena being explained, as well as the values of those that interpret them.

While differences still remain regarding the exact delimitation of these fundamental categories, their prolific use in both social science and popular discourse points to their usefulness in understanding social phenomena. However, in order for us to shape interactions in ways that are beneficial to organizations and to society, it is paramount that we share a clear and coherent view of what exactly it is that we are talking about. Hopefully this essay provides some useful material in that direction.

References and further reading

BARNEY, Jay B. (1986). “Types of Competition and the Theory of Strategy: Toward an Integrative Framework”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 781-800.

BASKOY, Tuna (2003). “Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of Business Competition”, Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 1121-1137.

BLAUG, Mark (2001). “Is Competition Such a Good Thing? Static Efficiency versus Dynamic Efficiency”, Review of Industrial Organization, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 37-48.

BRATMAN, Michael E. (1993). “Shared Intention”, Ethics, Vol. 104, No. 1, pp. 97-113.

BRIGANDT, Ingo (2010). “The epistemic goal of a concept: accounting for the rationality of semantic change and variation”, Synthese, Vol. 177, Issue 1, pp. 19-40.

DECLERCK, Carolyn H., Christophe BOONE and Griet EMONDS (2013). “When do people cooperate? The neuroeconomics of prosocial decision making”, Brain and Cognition, Vol. 81, Issue 1, pp. 95-117.

DEUTSCH, Morton (2006). The Handbook of Conflict Resolution. Second edition. John Wiley & Sons.

FAFCHAMPS, Marcel (2003). “Social Capital and Development”, Economic Series Working Papers, No. 214, University of Oxford,http://users.ox.ac.uk/~econ0087/manche.pdf

FRIEDMAN, Milton (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago Press.

GINTIS, Herbert (2011). “Gene-culture coevolution and the nature of human sociality”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Vol. 366, no. 1566, pp. 878-888.

HANNAN, Michael T. and Glenn R. CARROLL (1991). Dynamics of Organizational Populations: Density, Legitimation and Competition. New York: Oxford University Press.

HAUSMAN, Daniel M. (2007). The Philosophy of Economics: An Anthology. Cambridge University Press.

HAYEK, Friedriech A. (1949). “The Meaning of Competition”, in Individualism and Economic Order, London: Routledge.

HEATH, Joseph (2001). The Efficient Society. Penguin Books.

HEATH, Joseph (2006). “The Benefits of Cooperation”, Philosophy & Public Affairs, Vol. 34, No 4, pp. 313-351.

HEATH, Joseph (2007). “An Adversarial Ethic for Business: or When Sun-Tzu Met the Stakeholder”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 72, No. 4, pp. 359-374.

HENNART, Jean-François (1991). “Control in Multinational Firms: the Role of Price and Hierarchy”, Management International Review, Vol. 31, Special issue: Frontiers of International Business Research, pp. 71-96.

KINCAID, Harold (2012) (ed.) Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Social Science. Oxford University Press.

KRIPKE, Saul (1980). Naming and Necessity. Harvard University Press.

KOGUT, Bruce and Udo ZANDER (1993). “Knowledge of the Firm and the Evolutionary Theory of the Multinational Corporation”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 625-645.

LEIST, Anton (2011). “Potentials of Cooperation”, Analyse & Kritik, Vol. 33, Issue 1, pp. 7-33.

LIPSEY, Richard and Kelvin LANCASTER (1956). “The General Theory of the Second Best”, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 11-32.

MARTIN, Dominic (2013). “The Contained-Rivalry Requirement and a ‘Triple Feature’ Program for Business Ethics”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 115, Issue 1, pp. 167-182.

MAYNTZ, Renate (2004). “Mechanisms in the Analysis of Social Macro-Phenomena”, Philosophy of the Social Sciences, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 237-259.

MCNULTY, Paul J. (1968). “Economic Theory and the Meaning of Competition”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 82, No. 4, pp. 639-656.

NORTH, Douglass (1991). “Institutions”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 97-112.

PIENKOWSKI, Dariusz (2009). “Selfishness, cooperation, the evolutionary point of view and its implications for economics”, Ecological Economics, Vol. 69, No. 2, pp. 335-344.

PUTNAM, Hilary (1975). Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press.

THOMASSON, Amie L. (2003). “Realism and Human Kinds”, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 67, No. 3, pp. 580-609.

TRAPIDO, Denis (2007). “Competitive Embeddedness and the Emergence of Interfirm Cooperation”, Social Forces, Vol. 86, No. 1, pp. 165-191.

TUOMELA (1993). “What is Cooperation?” Erkenntnis, Vol. 38, Issue 1, pp. 87-101.

TUOMELA (2005). “Two basic kinds of cooperation”, in: Vanderveken, D. (ed.) Logic, Thought and Action. Springer. Chapter 4, pp. 79-107.

VICKERS, John (1995). “Concepts of Competition”, Oxford Economic Papers, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp. 1-23.