Economics tells us that selling is about understanding a customer’s needs and delivering a product to meet them. In the world of homo oeconomicus, the success of a transaction depends on what the customer is willing to pay, and the price at which the seller is willing to sell. As soon as there is a match, there is a sale. Management textbooks describe elaborate step-by-step sales procedures, as if sales were only about being organized and proactive.

In most real-world situations, however, sales are quite unpredictable. Potential clients must be courted, discussions must be initiated, trust must be gained, and unconscious needs must be satisfied. Successful sales thus depend on a variety of structural and psychological factors. This article intends to examine these factors in greater detail and incorporates different personal, professional and scholarly perspectives.

Structure and context

All sales are determined by the context in which the sale is performed, and the type of product being sold. As an illustration, Philip Delves Broughton asks us to consider two extreme ideal-type companies:

The first company “sells industrial equipment to a few hundred customers all over the world. It is highly profitable and has few rivals. Its sales force is well educated and well-paid. They don’t come up with products and try to bully them onto their customers. Instead, they are engaged in a long-term conversation, finding out what their customers need and then developed products to match their requirements. Each failure is considered an opportunity to learn.”

The second company sells “software solutions to small businesses. Prices are low and margins slim. Salespeople are paid solely on commission, without benefits. They must sit in cubicles under glaring fluorescent light and their calls are closely monitored. They must make at least eight calls an hour and are expected to close one in thirty pitches. Hiring and firing involves almost no cost to the company, so the high turnover rate is, from a managerial perspective, trivial. Employees find the work stressful and dehumanizing, but they have few choices in life.”

From a managerial perspective, both approaches work. What matters is context. According to Broughton, “the boiler room may be unappealing for its treatment of people, but for certain products and services sold as quick one-off transactions, it is enormously effective. The learning-oriented environment works when you need salespeople to build trust, to persevere in the face of difficulty, and establish real relationships with customers. Applied in the wrong setting, however, it can lead to a lazy, excuse-filled culture where sales are being constantly delayed and long-term profits are never realized.”

Psychology

The psychological aspect of sales refers to the “battle of wits, personality, and emotion between the seller and buyer.” This is perhaps the most important aspect of sales. In any industry where persistence is required to overcome adversity, a sense of optimism is vital. And yet sales is prone to a panoply of fears and social phobias. “Social anxiety makes people want to flee, to get out of the hellish nightclub or cocktail party. The salesperson cannot run. He is trapped until the sale is resolved one way or another.” Multiple rejections can easily cause a downward spiral of pessimism.

The psychologist Martin Seligman argues that bad social events, our interpretation of them, and how they affect our behavior, tends to fall into three categories.

First, we see events as either internal or external. Internal events are caused by us (“I lost my wallet because I’m an absentminded fool”), while external events are caused by a particular situation (“I lost it because we were in a mad rush to catch the next bus”). Second, we attribute events to stable or unstable factors. My losing the wallet is typical of how we travel, always leaving things last minute. Or, this was a one-off event, which is unlikely to happen again. Third, we categorize events according to global versus specific attributes. “The lost wallet symbolizes my life of incessant failure, disorganization, and futility” is a global attribution. Specific would be “Really, it’s just a lost wallet and once I’ve called my credit card companies and gotten a new driver’s licence, life will go on as before – no big deal”.

Building upon these insights, Peter Schulman, a professor at the Wharton School, identifies three psychological traps in sales: pessimism, irrational assumptions, and logical errors. Pessimism is the result of excessively internal, stable, and global attributions. Irrational assumptions include “I need to close every sale,” or “I cannot risk making a mistake.” Errors in logic include personalization, or assuming everything is about you. Your boss passes you in the hall without acknowledging you and you immediately assume you have done something wrong, when in fact he may have just learned his dog has died.

All of these traps can affect a salesman’s motivation. Too much optimism and the salesman risks becoming naïve and reckless, the kind of person that acts without reflecting on his mistakes. By succumbing to pessimism, he risks endangering both his career and mental health. There is thus a delicate inner balance to be achieved.

The importance of situational knowledge

Effective sales require highly tacit, pragmatic, situational knowledge – the kind of knowledge that academics know of, but can only dream of possessing. This can take several forms.

First, seasoned salespeople constantly identify and categorize customer attributes. For example, a customer who wears expensive clothes and drives a Ferrari is assumed to have plenty of money and to be eager to show it off. The novice salesperson will stop there. The more experienced one might look more closely. Perhaps there’s a button missing on the cuff, or the car could use a wash. Maybe this customer is not all he is cracked up to be. A novice might quickly assume stereotypical gender roles between a husband and wife, whereas experience would tell you who really makes the buying decision. The effectiveness of salespeople, then, depends on how accurately they rank such situational details in their mental hierarchy.

Second, the experience of salesmen pitching to executives in high-stakes situations has shown that many aspects of sales can be counter-intuitive, and that there is in fact a much wider range of acceptable behaviors than one might think. One can only get a feeling for what works and what does not through trial and error.

Think, for instance, of how you should pitch a deal to a senior vice president of a multinational company with a massive ego, a rude and arrogant behavior, and a complete lack of interest for you. The inexperienced salesman will be deferential, will start explaining himself and get into an elaborate argument, or even worse, will let himself be told what to do. He will be trapped within a ‘subordinate mindset’ imposed by a figure of authority. But this is wrong. The situation has to be reframed. The right approach is to be unreactive, use light humor, and make him qualify himself to you. This is not easy, but it will work if performed correctly.

To understand why, one has to recognize that our behavior acts as an indicator of our social status, and that people react to such behavioral cues on a deeply instinctive level. The experienced salesman effectively communicates that he does not give a shit about authority. He has something unique to offer, he has no time to waste, and he is willing to go to another client if needed.

The misunderstood probabilities of sales

Start-ups generally operate in an environment of high uncertainty when it comes to anticipating sales and revenue. Many follow best practices and plan their sales process as though they were big companies with established markets and customers just waiting to be cashed in. Prospective clients are sorted by sales stage and probability in nicely elaborated pipelines. Managers are told to concentrate their efforts on the “lowest hanging fruits.” But strangely no contracts ever seem to materialize as expected.

Managers tend to think they know which clients are most likely to invest in their product or services, and often decide to focus all their efforts and resources on those leads. Yet they might just end up being stuck with a small but fragile set of “promising” prospective clients, which then turn out to be bad apples, bringing the entire sales effort back to square one.

An insight I gained from reading Taleb is that, more than other firms, start-ups operate in an “opaque” environment: they have limited knowledge of changing market conditions; they are often not fully aware of what goes on within client organisations and what motivates the clients’ purchase decisions; they often do not have all the information required to bring contract negotiations to close; their hopes for revenue accordingly tend to fluctuate wildly from one month to another.

Consider the following. I once witnessed a painful situation where a major client in the Middle East was about to sign a contract for a highly significant project. He had been discussing with our engineering team for well over a year, paid for an engineering study to fully confirm the feasibility of the project, and was regarded as a top sales priority to which the company dedicated considerable time and resources. But last-minute discussions between the client and public agencies revealed that the project would be more complicated than anticipated due to regulatory barriers that everyone had overseen. The client promptly informed us he would not proceed with the project.

Even after a sale has been concluded, projects are still at risk of vanishing. I once closed a solar project in Greece, only to learn a few days later that the government had forbidden all outbound transactions from Greek banks, meaning our client could not pay us upon signature, even though the money was there. Nobody saw that coming. For a moment, we thought we were fucked. Luckily for us the crisis subsided, and the project was commissioned in the ensuing year.

To assume that each subsequent stage in the pipeline leads to a higher probability of sale is wrong and misleading. There are simply too many unknown factors affecting a client’s purchase decision, even at advanced sales stages, for any reliable probabilities to be determined.

A better approach for start-ups is to assume that the most promising clients, those where you’re almost there, still have at least a 50% chance of being lost. Would you then spend all your resources on those few advanced sales leads? No. You would probably also spend some time on finding and nurturing additional backup leads. If your product is viable, there will be others out there.

Your market does not exist. It must be created.

High-tech ventures are subject to the following fundamental attributes. First, startups selling disruptive technologies rarely have an established market: few people are aware that the product exists, and even if some do hear about it (assuming you have the equivalent of Elon Musk’s public relations machine), they rarely understand how it works, and thus do not fully understand the value it offers.

Second, new technologies are nearly always perceived as risky, and not without reason: many new promising technologies fail spectacularly. The more capital-intensive the technology, the higher the risk. Inexperienced firms will be unaware of important market conditions, which they only learn about at the last minute. Their product often ends up being more complex than anyone, including the founders, ever believed, especially when the moment comes to implement it in a real-world commercial setting. The client’s perception of risk often cannot be minimized unless prototypes, demonstrations, discounts, guarantees, financing and other creative solutions are offered to mitigate initial concerns.

Sales will never scale up unless initial clients’ risk perception is overcome. There may be “early adopters” with a higher acceptance of risk, but even if they exist, they also have their limits. In this regard, sales are all about knowledge transfer. The complexity of high-tech products implies that the sales team must constantly educate potential customers and partners about the value they can offer. This often eats up more time than expected and can easily slow down the sales process. High-tech start-ups must therefore design a sales system that can drive this outward learning process as efficiently as possible.

First survive, then grow.

Obviously, many young firms face important financial and budgetary constraints with regards to headcount. Considerable resources must be spent on developing and creating a viable technology. And there is limited cash in the coffers to support the sales effort. This is all very understandable.

But problems arise when companies become subject to a product development bias, particularly common among startups run by engineers. They spend too much on product engineering and too little on marketing and sales. Symptoms resulting from this skewed resource allocation include a thin pipeline, too few prospects that materialize into contracts, and a general failure to reach sales objectives. This is typically exemplified by the company working hard to design a perfect product, only to realise too late that it does not sell as expected.

Make no mistake: sales are not just about putting a product on the market; they are about survival.

It is entirely possible to sell an imperfect or defective product. In fact, to avoid ruin, this is what many start-ups should do. By selling minimally viable products, they save time and obtain valuable operational feedback, which in turn allows them to make quick iterative fixes to their product design, bringing it closer to maturity, which in turn provides the sales team with additional arguments to confront the market.

But this brings up another issue, namely the risk that a company faces when it sells a defective product. This risk can be very high for capital-intensive projects, where one big mediatized failure can literally kill a company. Such risks are important, but must always be weighted against the risk of perishing in the valley of death. Ultimately it is better to sell a defective product than to starve: at least it buys you some precious time.

Recent research of bankruptcies among start-ups with access to venture capital suggests that most had invested in building something nobody wants because they had the money to actually build it, and then ran out of cash, as they were unable to generate stable revenue. This confirms the risks linked to the product development bias, which disconnects the firm from actual market needs, and which can be amplified by easy access to venture capital.

Correctly sizing and building a sales team

How many salespeople do you hire? How do you drive your sales force? Although there is no universal solution to these questions, I believe there are some rules of thumb that most high-tech startups can benefit from.

I am a proponent of the idea that startup companies with sizable ambitions should have a “war room,” that is, a room for sales only. They should staff that war room appropriately. Find the brightest, most talented, most motivated salespeople out there; train them, incentivize them, and tell them to kill it. Make it fun.

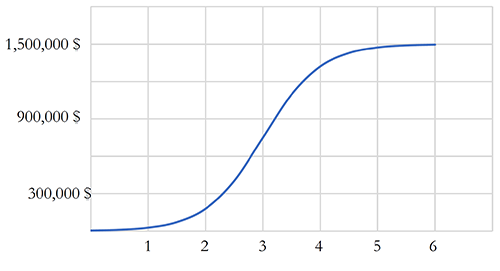

The number of salespeople to hire depends on what your finances allow, as well as the expected marginal return on each hire. A good way to assess the latter is to estimate your sales response curve, as illustrated in the figure above. The curve shows how yearly revenue is expected to vary with the number of sales managers hired. Most startups do not have any historical data to calculate this type of function and would instead rely on limited managerial insights.

During early growth stages, there should be a core team of senior managers with a focus on the most lucrative and strategically important commercial proposals, whose responsibility is to drive these proposals to negotiation and closure.

This core team should be made up of competent, tireless world-class closers, supported by the company’s technical specialists when needed. The core team should be surrounded by several salesmen working tirelessly on finding and educating new potential buyers. Their responsibility should be to drive sales by increasing volume, meaning the number of interactions the company has with potential buyers. The higher the volume of interactions, the higher the probability that some leads will materialize into contracts.