We may sometimes feel confident enough to cross a line beyond which there is no return. But what is the actual relation between confidence and success? Can we really say that Caesar was successful after crossing the Rubicon because he was confident? And subsequently, that he became a victim of his own success, and that he was assassinated because he was overconfident? Is there such a thing as a right level of confidence? Phil Rosenzweig offers a rigorous answer to these questions in his book Left Brain, Right Stuff.

The illusion of overconfidence

Rosenzweig made an extensive search for the words “overconfident” and “overconfidence” in the business press. His statistics indicate that “by far the most common use was retrospective, to explain why something had gone wrong.”

In most of the examples he came across, “from politics to natural disasters to sports to business, overconfidence offers a satisfying narrative device. Take any success, and we can find reasons to explain it as the result of healthy confidence. We nod approvingly: They were confident—that’s why they did so well. Take any failure, and we shake our heads: They were overconfident—that’s why they did so poorly. If they hadn’t been so sure of themselves, they might have done better.”

There’s an appealing syllogism at work:

- Things turned out badly, so someone must have erred.

- Errors are due to overconfidence.

- Therefore, bad outcomes are due to overconfidence.

Rosenzweig points out that this reasoning is deeply flawed. First, “not everything that turns out badly is due to an error. We live in a world of uncertainty, in which there’s an imperfect link between actions and outcomes.”

Second, “not every error is the result of overconfidence. There are many kinds of errors: errors of calculation, errors of memory, simple motor errors, tactical errors, and so forth. They’re not all due to overconfidence.”

Humans are not intrinsically overconfident, as much literature in behavioral economics would suggest. Rather than claiming that leaders are biased, Rosenzweig believes it might be more accurate to say they are myopic. “They see themselves clearly, but have less information about others, and generally make sensible inferences accordingly.”

The problem with behavioral economics is that it analyses human decision-making under extremely specific and controlled conditions. This makes findings easy to replicate. However, real-life decision-making happens in much more complex situations and unfolds dynamically over much longer periods of time. “Most of the time, we tell ourselves I’m confident or I’m doing well. But then, in a moment alone at home, you feel how close you are to some kind of abyss.”

Henry David Thoreau once claimed that many people live “lives of quiet desperation,” appearing confident and determined in public, yet full of existential questions in private. “We live in a society that is impressed with confidence, and we often try to project confidence because we think others expect it of us. But when we look closely at the evidence, it’s questionable whether people are best described as exhibiting overconfidence.”

A question of mindset

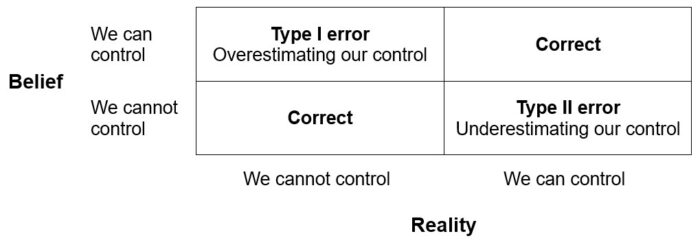

Taking risks involves a dilemma with regards to our mindset. We want to avoid being a naïve optimist (type I error), but we also want to avoid defeatist pessimism (type II error), as Phil Rosenzweig illustrates in the following table:

How do successful business leaders avoid these two errors in practice? In other words, how do they make sure that their beliefs match the requirements of reality?

While this is an interesting question, it can also be misleading. The reason for this is that success does not always require that we form true beliefs which correspond to reality. In the business world, the only thing that matters is that our mindset increases our probability of success for the situation we find ourselves in — it does not really matter whether our beliefs are true. Being a naïve optimist can actually be beneficial in certain situations.

The question we should ask is whether the situation we are facing calls for high levels of confidence; and whether we can adapt our mindset depending on the situation that we are facing.

The psychologist Peter Gollwitzer “distinguishes between a deliberative mindset and an implemental mindset. A deliberative mindset suggests a detached and impartial attitude. We set aside emotions and focus on the facts. A deliberative mindset is appropriate when we assess the feasibility of a project, plan a strategic initiative, or decide on an appropriate course of action.”

When we are in a deliberative mindset, we take a step back to behold and analyze the world, before carefully considering the best course of action based on the available evidence. This is essentially a cautious approach, not one that we would associate with confidence and courage.

“By contrast, an implemental mindset is about getting results. When we’re in an implemental mindset, we look for ways to be successful. We set aside doubts and focus on achieving the desired performance. Here, positive thinking is essential. The deliberative mindset is about open-mindedness and deciding what should be done; the implemental mindset is about closed-mindedness and achieving our aims. Most crucial is the ability to shift between them.”

“The question we often hear – how much optimism or confidence is good, and how much is too much – turns out to be incomplete,” says Rosenzweig. “There’s no reason to imagine that optimism or confidence must remain steady over time.”

Different types of situations call for different types of mindset. A good example of a situation requiring an implemental mindset is that of the pilot Chesley Sullenberger, when he decided to ditch his passenger airplane into the Hudson river after both engines were suddenly disabled by a bird strike.

“The water was coming up fast,” he recalled. When asked if during those moments he thought about the passengers on board, Sullenberger replied: “Not specifically. I knew I had to solve this problem to find a way out of this box I found myself in.”

He knew exactly what was needed: “I had to touch down the wings exactly level. I needed to touch down with the nose slightly up. I needed to touch down at a decent rate, that was survivable. And I needed to touch down at our minimum flying speed but not below it. And I needed to make all these things happen simultaneously.” At all times, he said, “I was sure I could do it.”

It might be that confidence is not a sufficient condition for success; but Sullenberger’s case shows that there are situations where confidence is necessary. As we will see, this makes it incredibly difficult to judge whether someone who appears confident will actually succeed.

Why appearances matter

The Harvard sociologist Rakesh Khurana made a study of CEO selection, in which he discovered that “the market for CEOs was fraught with imperfections and largely based on highly subjective perceptions.”

He describes the process of executive search as “the irrational search for a charismatic leader,” which Rosenzweig says is best understood as “a ritual in which boards of directors make choices that appear to be reasonable and be defended no matter how things eventually turn out.”

“Because leaders cannot easily be assessed on what should matter most – the quality of their decisions – they are often evaluated on whether they conform to our image of a good leader. Above all, it helps to have the look of a leader.”

In other words, the market for CEOs is in large part a market of theatrics. Rosenzweig believes somewhat cynically that “leaders come to appreciate the importance of perception through their own (sometimes painful) experience. They have learned – often the hard way – that results only count for so much.”

Chief executives “know their decisions will take years to play out and will be confounded by so many other factors that a definitive evaluation will be close to impossible. As a consequence, they often act with an eye toward how they will be perceived. They try to conform to what we associate with effective behavior, chief among which is to appear decisive.”

Many of the problems that end up on a CEO’s desk will not have any obvious solutions. Executive decision-making often implies a form of risk management, being all about gaging the upside and downside of different options.

While the long-term consequences of such decisions are generally very difficult to assess, in the short-term the leader will often be judged solely on his or her confidence. CEOs know that “they’ll be perceived as performing well as long as they seem to be inclined toward taking action and acting with self-assurance.”

However, decisiveness is not the only quality that leaders try to act out. Another apparent quality that they will seek to display is persistence, because they are generally expected “to have a clear sense of direction and to be steadfast in the pursuit of associated goals.” In fact, “the desire to be seen as persistent helps explain why decision makers are prone to escalate their commitment to a losing course of action.”

Why leaders act this way is not necessarily due to bad intentions. It may simply be due to their belief that persistence is an attribute that is required from a leader, and that such an attitude is expected from their board. “What seems to the leader like a reasonable decision – to take just one more step, perhaps a small one, and to remain persistent, disciplined, and steadfast – can lead to a disastrous outcome.”

Making winning decisions is hard

The decisions that leaders face are not simply a matter of deliberate practice or accumulated know-how. They often require a solution that is unique to the situation at hand. These decisions are, almost by definition, “more complex and consequential than routine decisions” made by other individuals.

Leadership is defined by one’s capacity to influence people. “Leaders mobilize others to achieve a purpose, which means that they do their work through the actions of other people. Leadership means shaping outcomes, which involves exercising control, of which we often have more – not less – than we imagine.”

Great captains can navigate their ships with skill and command immense respect from their crew, but that does not mean that they always achieve their targets. Rosenzweig draws several implications with regards to how leaders make winning decisions:

“First is to recognize that they need to instill in others a level of confidence that might seem exaggerated, but is necessary for high performance […] Ultimately, the duty of a leader is to inspire others, and for that, the ability to personify confidence is essential.” The point here is that one cannot only score high on technical skill; one must also project the right appearance of strong will and determination, and communicate this in a manner that motivates others to do their best.

Second, “unlike the decisions that offer rapid feedback, so that we can make adjustments and improve for the next one, leaders often make decisions that take a long time to bear fruit. Deliberate practice is impossible; leaders often get only one chance to make truly strategic decisions.”

“Third, because it is difficult to evaluate complex and long-term decisions with precision, leaders often act with an eye to how they are expected to behave. Put another way, they decide how to decide. When in doubt as to the best course of action, leaders will tend to do what allows them to be seen as persistent, as courageous, and as steadfast” even though that might not always be the best course of action.

“At its core, however, leadership is not a series of discrete decisions, but calls for working through other people over long stretches of time.” The “consequential decisions leaders face are fundamentally different from what has been studied at length in laboratory settings” of behavioral economics.

The winner’s curse

Another interesting question for executive decision-making is whether winning – that is, ending up first in a contest – should always be equated with success. Have you ever witnessed a confident and driven person win a competition, but then regret the outcome?

The phenomenon whereby a winning bidder may end up losing money is known as the winner’s curse. It was first identified as a phenomenon in the oil industry in the 1960s. When American companies reviewed the performance of their oil leases, they found out that “virtually every company that acquired oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico through public auctions ended up losing money.” Winning bids had turned into unprofitable investments.

One researcher, a geophysicist called Ed Capen, found that the cause was due to the auction system itself. He discovered “an insidious dynamic: when a large number of bidders placed secret bids, it’s almost inevitable that the winning bid will be too high.”

“The winner’s curse is particularly important in the world of finance,” says Rosenzweig, where “it poses a serious danger for investors in publicly traded assets. Because market analysts and investors have access to roughly the same information, anyone willing to pay more than the market price is very likely paying too much.”

“The implication is sobering. Imagine you spot what seems like a bargain – a stock that you think can be bought on the cheap, for example. Rather than believe you know something that others don’t, it’s wiser to conclude that you’re wrong.”

Rosenzweig points to the fundamental difference between two types of auctions. The first is common value auctions, while the second is private value auctions.

In common value auctions, the value of the asset being sold is objectively the same for all bidders. It is possible that bidders may have different information about the asset; but if they did have the same information, they would all bid the same price. Imagine that there is a jar filled with identical coins, and that the jar is sold to the highest bidder along with its contents.

The value of the coins is the same for all participants, so everything depends on participants’ assessment of how many coins are in the jar. What tends to happen in such auctions is that most participants will estimate the value of the jar’s contents correctly. But a few bidders will likely overestimate: they end up winning and they also end up overpaying. They suffer the winner’s curse.

The publicly traded stock of Apple or Microsoft is similar in nature to the coins in the jar. Both are financial assets that generate a specific “objective” future cash flow. We may have different estimates of what that cash flow is; but ultimately neither you nor I can influence its value.

For these kinds of assets, says Rosenzweig, “there’s nothing to be gained from anything other than careful and dispassionate assessment.” The auction requires a deliberate mindset. You wouldn’t worry about losing this auction, or committing a Type II error. “You should worry about making a Type I error – winning the bid and realizing you have overpaid.”

In private value auctions, the value that is gained from the asset being sold can vary for different buyers. Why we would value the same object differently can be entirely due to subjective reasons, as in the case of a collectible item. Another reason is that we might be able to influence its future value in different ways.

This is definitely the case for corporate acquisitions. When a big company buys a smaller company, the transaction is a matter of private value, not common value. “Value isn’t captured at the point of acquisition, but is created over time.”

Empirical research by the M&A expert Mark Sirower shows that most acquisitions fail to create value. Analyzing more than a thousand deals between 1995 and 2001, all of them valued over 500 million USD, his research found that 64% of acquisition investments lost money. “On average, the acquiring firm overpaid by close to 10%.” On the flipside, a significant number of acquisitions – 36% – were profitable.

Rosenzweig believes that successful buyers managed to “identify clear and immediate gains, rather than pursuing vague or distant benefits. Also, the gains they expected came from cost savings rather than revenue growth. That’s a crucial distinction, because costs are largely within our control, whereas revenues depend on customer behavior.”

These buyers were effectively able to generate more value from the acquisition than what competing bidders believed they could make from the deal. The ability to create synergies in operations, as well as the acquired firm’s potential to affect the buyer’s competitive position in the market are all aspects of the bid that are unique to each buyer: they are a matter of private value.

“When we can exert control, when we must outperform rivals, when there are vital strategic considerations, the greater real danger is to fail to make a bold move. Acquisitions always involve uncertainty, and risks are often considerable. There’s no formula to avoid the chance of losses. Wisdom calls for combining clear and detached thinking […] with the willingness to take bold action.”

In these types of situations, it might be preferrable to risk “making a Type I error – trying but failing – rather than a Type II – not trying at all.” Rosenzweig illustrates this by looking into a specific case of a private value auction: a bidding war for a construction project.

The case of Skanska

In 2009, the National Security Agency (NSA) announced its plans to build a new computer facility, the Utah Data Center (UDC), for storing and analyzing the security information it gathers around the world. The facility would be “fully self-contained, with its own power plant and water supply, and would come equipped with anti-terrorism defenses.”

But someone would have to build it. A huge construction contract was tendered out to private contractors. One of the bidding companies was Skanska USA Building. Skanska was “a leader in the North American construction industry. It had a strong record of large and successful projects.” The UDC was very attractive to Skanska, because it was a “design/build” project, meaning that the contractor would handle both design and construction.

After preliminary bids had been received, the government retained the top five contenders and asked for a final improved offer from each of them. It also made it clear that it would not consider any bid above $1.212 billion; contractors would have to keep their costs below this limit.

Skanska’s president at the time, Bill Flemming, explained that “if you can come in with a better design – more efficient and smarter functionality – and if you have methods to build the facility faster, then you might beat the other bidders.” This was a situation in which “an aggressive bid was surely needed, but a danger loomed: if Skanska made a very low bid in order to win, it would very likely end up losing money.”

“There was much to admire about the way Flemming and his team approached their task,” says Rosenzweig. “They tried to separate what they could control from what they could not. They didn’t get carried away with the optimistic inside view, but gave explicit consideration to the outside view. Flemming had learned that for a large project, another 3% in cost reductions were realistic, but expecting more was doubtful.”

“At the same time, he knew that success comes to those who are willing to take a chance. He was prepared to make a bid that went beyond that. Flemming was also keenly aware of his role as a leader. He understood how his decision would reflect on him and his company, and he wanted to be seen as aggressive but not reckless.”

“He thought about the relative implications of Type I and Type II errors. Given Skanska USA Building’s current performance, winning the UDC contract was desirable but not essential. It was better to make a strong effort but come up short than to take an outsize risk and lose money.”

“On the night of August 12, 2010, after intense deliberations, Flemming settled on a bid of $1.2107 billion, just $1.3 million below the government’s limit of $1.212 billion.”

“Five weeks later, on September 25, the Army Corps of Engineers announced its decision: the UDC contract was awarded to a three-way joint venture of DPR Construction, Balfour Beatty, and Big D Construction. Their winning bid of $1.199 billion was $12 million lower than Skanska’s figure. A different of just one percent, but enough to win the contract.”

At Skanska, the news was met with immense disappointment. Many people had worked on the bid submission for weeks, all for nothing. Skanska executives asked themselves what they could have done differently.

“I don’t think we missed anything, or that we could have taken a bigger chance,” said Flemming. “I felt we took as much of risk as we could have. Maybe we could have found another $5 or $6 million, but never enough to get to [the] low bid.” In the end, even without the UDC contract, Skanska USA Building went on to post excellent results in 2010 and 2011.

To learn more, Rosenzweig contacted one of the winners, DPR. The company is highly regarded and has many schools, hospitals, and corporate offices in its portfolio. The year after the UDC tender, Facebook chose DPR to build its first European data centre in Sweden. Rosenzweig spoke with two executives closely involved in the UDC bid process.

“When the NSA first announced the UDC in the summer of 2009, DPR had been very eager. It had the experience and skills to make a strong bid. It had been one of twelve to submit an RFQ in February, and one of five invited to bid. From there, it assembled a strong team to prepare a winning proposal. Its first bid, in June 2010, was around $1.4 billion.”

“When DPR was given the NSA’s new target of $1.212 billion, it devoted long hours to reach that limit. It worked with its subcontract partners to reduce costs. It went over the design in excruciating detail, looking for ways to simplify whenever possible while still meeting the technical specifications. Like Skanska, DPR reduced its risk contingency and looked for ways to shave its management fees. It was a very arduous process.”

“By early August DPR’s bid stood at $1.227 billion, now very close but still about $11 million over the target. At that point DPR also considered the likely bids of its rivals. Barely squeezing in under the limit wouldn’t be enough; it wanted to make sure it would come in below the others.” Gavin Keith set a target of $1.198 billion, which represented a total of $23 million in savings compared to their latest estimation. This target was, as he put it, “a gut feeling based on experience.”

The DPR team worked relentlessly to achieve this target but did not fully secure all the savings they wanted; they were still missing $10 million. However, they also managed to identify a number of potential sources of savings. When Keith was “satisfied that a combination of elements should let them find $23 million in savings, they submitted a bid of $1,198,950,000.”

He made the call to cross the Rubicon. The die was cast; there was no way back.

“When DPR learned it had won, its first reaction was elation. Very soon that gave way to the sober realization of the immense task ahead.” While the project was not executed without challenges, by 2013 it was on track and meeting its milestones for completion. How did they manage to pull it off?

For Rosenzweig, the explanation likely lies in the combined strengths of the joint venture consortium.

“DPR’s experience with data centers gave it a slightly lower cost base. Furthermore, Balfour Beatty’s successful experience with Army Corps of Engineers projects was vital in addressing key government requirements, and Big D, a Salt Lake City contractor, brought valuable insights about the local labor market. Together, these advantages provided a crucial edge, and allowed them to enter August needing only $10 million in further savings to reach their target, compared to $48 million for Skanska.”

Key lessons

What is impressive, both for Skanska and DPR, is the extent to which executives combined extensive preparation with a strong gut feeling to make a final decision. In the situation they were in, no scientific formula could ever have provided them with a fully calculated correct answer. “Yet neither did they make a blue-sky guess, in which any number was as good as another […] a great deal of time and effort was devoted to careful and objective analysis.”

The best managers understand that they must switch between analytic and intuitive mindsets, with varying levels of confidence. They also understand that they must sometimes take calculated risks, even if that implies that they might not make it. Once they cross the Rubicon, they act as if nothing is left to chance anymore, and everything depends on their ability to motivate their team to achieve the best possible outcome.