It is fascinating to observe how people become obsessed with their reputation. This is especially true in the era of social media. I find this fascinating because I believe that reputation is something that is very hard to control: it takes time to build, but can easily crash. Moreover, I have always thought that people who are excessively concerned about their image easily become false and superficial; and that caring too much about reputation makes you a slave to the opinions of others.

So why is it that reputation is such an important concern in our societies? The Italian philosopher Gloria Origgi offers a fresh and extensive understanding of reputation as a psychological and social phenomenon in her book Reputation: What It Is and Why It Matters. I here summarize some of the main points made by the author.

The nature of reputation

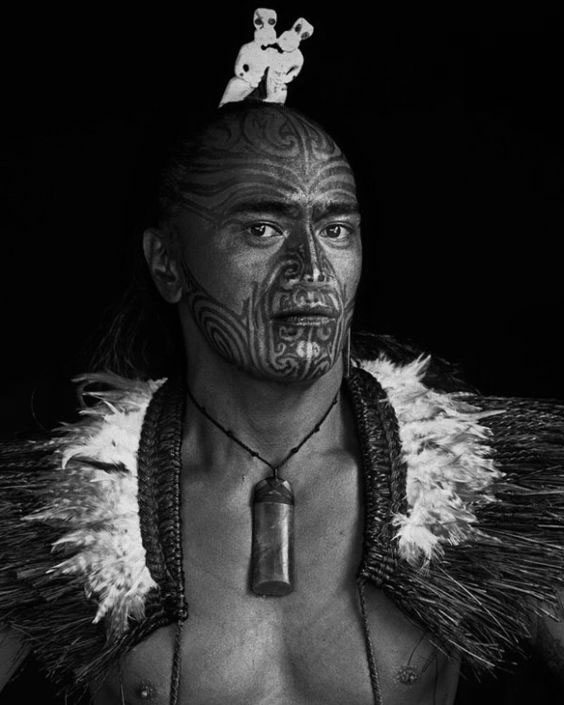

Origgi claims that “all of us have two egos, two selves.” One is our subjective self, informed by our physical sensations. “The other is our reputation, a reflection of ourselves that constitutes our social identity and makes how we see ourselves seen integral to our self-awareness.”

It goes without saying that few among us would want to live as a hermit. But it is disconcerting to realize the extent to which we actually depend on, and live through, other people. Our social self “controls our lives to a surprising extent (…) the feelings that it provokes — shame, embarrassment, self-esteem, guilt, pride — are both very real and very deeply rooted in our emotional experience. Biology demonstrates that our body responds to shame as if it were a physical wound, releasing chemical substances that provoke inflammation and a rise in the level of cortisol.”

Much of our social self seems to be the result of our progression as actors. We “proceed by trial and error, experimenting with different selves, erecting a series of façades that turn out to be nothing but provisional drafts. When we see the effects that these invented selves have on others, we go back to the drawing board and try to fashion a different social image. Either that, or we give up and acquiesce in the picture that others have of us when we realize that we can’t control it anymore. The bitterness that accompanies a ruined reputation, the Proustian anxiety about our always uncertain social standing, and the deep ambivalence that these feelings evoke are due to our fundamental incapacity to keep our double on a tight leash. The shadowy reflection of ourselves that exists solely in the minds of others is ultimately impossible to control.”

How we think we are seen seldom reflects how we are actually seen.

The author goes on to say that “our social image is both familiar and strange. The reactions it provokes in us are largely involuntary, such as blushing before an intimidating audience. Although the way we see how others see us can occasionally cause us to lose control, it is, at the same time, the part of ourselves we prize most highly and on which we lavish the tenderest care.”

Reputation is both the means and ends of many human endeavors. “We try to manipulate how other people see us, taking our idea of how they see us now as a starting point.” This leads to “an arms race, an escalation game of believing and make-believing, of manipulating other people’s ideas and being manipulated by them in return. We all know the feeling of triumph that we experience when we think we have been appreciated for what we are really worth. Previous humiliations are erased; the world recognizes us at last as we always knew we deserved.” We are also far too familiar with “the opposite feeling of letdown and defeat when we capitulate before the disdain of others — when we are humiliated and belittled but nevertheless accede to their unfavorable way of measuring our worth.”

One of the underlying themes of Origgi’s work is that reputation is a beast that is difficult to tame. She observes, again and again, “the inherent fragility and even futility of our most determined endeavors to control how we are seen.” In fact, “the results of our serial attempts to manage how others see us are highly uncertain; yet they can sometimes be quite spectacular. The uncertainty of the outcome, in fact, is what makes the reputation game so endlessly fascinating.”

How reputation emerged

Looking back at how we evolved as a species, one curious fact stands out: humans are “not content with bookkeeper-style altruism of the I’ll scratch your back, you’ll scratch mine variety. We often behave altruistically toward total strangers. We can cooperate with people we will never see again.”

Origgi writes that indirect reciprocity provides a possible explanation for this. On the one hand, “the beneficiary of an act of altruism can be inspired to act altruistically” towards others. On the other hand, a person’s reputation for altruism may inspire others to return the generosity.

From an evolutionary perspective, “the emergence of reputation (including reputation for altruism) can be explained by its role in facilitating indirect cooperation. Social cooperation is possible only because people speak to each other about each other, and are thereby constantly making, remaking and unmaking the social image of everyone involved in the process.”

Hence “social emotions such as shame, indignation, guilt, and moral disapproval are the result of a uniquely human proclivity to take an interest not only in interactions in which we personally participate, but also in those that do not concern us directly. Indirect reciprocity is specific to human society and, on this theory, provides the basis for the evolution of moral norms.”

“That which principally preoccupies our minds is our ceaseless evaluating of the actions of others, evaluations undertaken partly in an effort to understand how the people we observe are likely to interact with each other in the future.” According to Origgi, “all morality, arguably, depends on reputation,” because moral norms “emerge and gain their binding power” only through people’s evaluations “of each other to each other.”

This is as true today as it was in ancestral times: our constant public evaluation and recognition of virtues, and shaming of vices, is what allows a sufficiently moral community to exist. Even today, our societies rest upon a fragile equilibrium of mutual trust and respect for the law. Formal institutions of justice are important, but they depend on informal moral norms — the law only delivers justice because most of us actually follow the rules. Anyone who has traveled to the developing world will know that formal institutions are completely dysfunctional when corruption is the norm. This is where reputation can play an important role. We should not be afraid to shame people who exploit public resources for their own private benefit.

False signals

Problems arise when people promote themselves as having qualities which they do not really possess. “The hallmark of reputation is that it can be communicated: who says what about whom? Signaling theory helps explain how we can strategically exploit the fact that our behavior always tells others something about us. It is built on the fundamental asymmetry between what the transmitter of a signal and what the receptor knows.”

Most of what is important to know about others — honesty, reliability, efficiency, wealth, intelligence — is empirically unobservable.

From an analytical perspective, it is useful to distinguish between signs and signals. Signals are produced intentionally. They are often used to deliberately communicate a certain quality. Signs, however, are unintentional. Speaking with a foreign accent is usually a sign. That is, unless I deliberately speak with an accent, in which case my audience may misinterpret a signal for a sign. Signs matter more than signals, insofar as they provide an honest cue about individual qualities.

This distinction is sometimes contradicted by social scientists like Veblen and Bourdieu, for whom “individuals produce signals no more intentionally than do peacocks. What individuals falsely believe to be their signals are, seen realistically, nothing but expressions of their place in the social hierarchy.” In his seminal book The Theory of the Leisure Class, Veblen “argues that leisure is a way for a dominant social class to signal its wealth. Highly developed athletic skills or mastery of ancient languages is a sign that its possessors have plenty of time on their hands. These are luxuries that only the wealthy can afford.”

This might be true for signals that pertain to status, which may depend on one’s economic conditions, but it is not true for signals that relate to moral agency and character. How does one differentiate a decent person from a charlatan?

Imagine a company that must hire an experienced and competent executive for a critically important position. A good recruiting process is essentially designed to evaluate the signals communicated by the candidate. Is this candidate really as good as he seems? How do you know if what is written on that resume is, in fact, true? Psychological tests and unexpected questions are all meant to catch the candidate off-guard, so that one may look beyond his persona (Latin for mask) to catch a glimpse of his real self.

A false reputation is quickly lost when tested.

— Xenophon

Origgi believes it is difficult to distinguish real from fraudulent signals, except for those that cannot successfully be feigned: these are called honest signals. An example of this would be an architect that decides to live at the top floor of a skyscraper that he has designed (Nassim N. Taleb would call this skin in the game.) “Honest signals are believable to the extent that few can afford to imitate them. Faking such a signal would normally cost too much.” This means that we should look for signs and honest signals, while remaining cautious of people who otherwise flaunt their qualities.

The spread of words

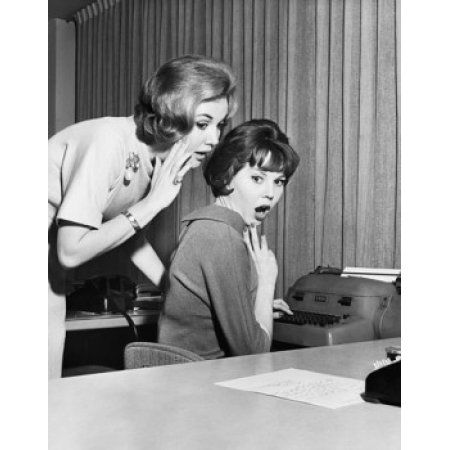

Another problem with reputation is its unpredictable development, since we cannot directly control how people talk about us. We can all potentially become victims of the rumor mill. Origgi believes that the “risks associated with rumors that spread uncontrollably result from two main factors.”

“One is our cognitive facility for social learning, that is, for employing cognitive heuristics that lead us, like apprentices copying their masters, to espouse the beliefs of others in order to acquire information and learn faster. The second factor is the social constellation that permits the diffusion of this information”. This depends on “who is the first to put this information into circulation and on their desire to acquire prestige by inducing others to adopt their point of view.”

Examples abound of large corporations paying celebrities (Brad Pitt, Monica Bellucci, George Clooney) to promote their products. “Marketing experts know how to exploit our disposition to learning by imitation, which translates into our easy acceptance of various heuristics. One such easily exploitable rule of thumb is the imperative to follow the leader.”

According to evolutionary psychologists, “this heuristic corresponds to an actual prestige bias, whose stability within our evolutionary history is due to its huge advantages for helping apprentices learn. Some of the most desirable skills are highly difficult to acquire.” Rather than analytically breaking down a skill into a large subset of codified step-by-step tasks, like a recipe, learners are “better off imitating their model in its entirety, thereby copying not only the elements that contribute to the master’s success, but also those that have nothing to do with it.”

As another example, “the simple fact that an individual finds himself to be a member of a class or high-status group — which might result from a purely statistical distribution — is interpreted as a causal relation. If someone is in that class, it must be because he possesses certain qualities. This bias constitutes a highly useful cognitive resource, and is a very economical way to manage information that can prove particularly useful in situations where we must make a decision one way or the other but where both information and time are scarce.”

Gossip, the activity whereby humans casually talk about others, also provides interesting clues about the way we are wired to interact. Gossip has a unique linguistic structure, which differentiates it from other types of discourse. It is usually introduced with “It seems that,” or “They say that,” which are called evidential constructions. “Evidentiality is a property of language, present in all tongues, that indicates the degree of control that the speaker exercises over events.” This is different from epistemic modality, which indicates the degree of certainty that something is in fact known, with expressions such as “It is possible that.” The authority of gossip operates at a different level: “not factual authority but a social authority.”

All of this indicates that uncontrolled rumors — otherwise known as informational cascades — are generally due to an environment in which people apply heuristics that are “perfectly legitimate” from an evolutionary standpoint.

Homo comparativus

Orrigi observes that “rivalry for material wealth is less intoxicating than the race for fame and reputation. Competitors for reputation need superior social skills, not merely financial virtuosity. To best their rivals, social animals must make alliances and stabilize hierarchies. The ultimate aim in all this is ‘to exist,’ to be present, to be visible, to shine brightly in the eyes of others.”

More than anything else, our species should be called homo comparativus, an animal whose actions depends on its relation to others, and who has a “crying need for recognition and approval. Human beings are neither essentially competitive nor essentially cooperative: they are comparative, that is to say, born and bred to draw comparisons and contrasts between themselves and others.”

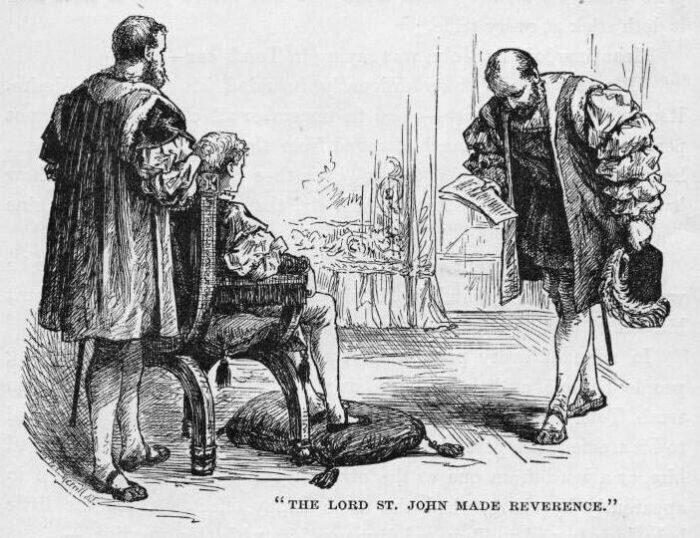

If social reputation motivates human behavior, it “is eminently dynamic, changing from interaction to interaction. In our society, reputation has become highly fluid and context dependent. Honor and reputation emerge from the dynamics by which relative status is created and maintained in hierarchical societies. These dynamics provide the basis for our capacity to make comparative evaluations: who is superior to whom.”

Human relations are, to a certain extent, inherently hierarchical. “The status of persons is influenced by those with whom they routinely associate (…) The uncertainty surrounding social ascent and descent generates anxiety regarding the status and fear of ‘dangerous’ social relations.” She goes on to say that “when we act in a way that displays our esteem for others we are establishing social hierarchies; but, in doing so, we are also changing our own social position.”

Does this mean that hierarchical status dynamics simply work in a one-way direction, where everyone at the bottom reveres those at the top, who end up amassing permanent privileges? Not quite. “Acts of deference that distribute honor, prestige, or reputation demand a certain degree of reciprocity (…) Those at the top of the pyramid must from time to time return the favor — without exaggerating, of course, because the difference between a leader and a follower is signaled by the asymmetrical nature of their relationship.” Even rock stars must occasionally signal that they love their fans.

In fact, “if someone that we admire never returns the favor (…) we will end up forsaking him or her. We love to recognize those who recognize us in turn,” even if we realize that the relationship is not one of equals. The innumerable acts of deference that we observe around us in daily life “increase asymmetries by amplifying initial differences of merit.” Origgi contends that these two mechanisms — social amplification and our need for at least a week form of reciprocity — largely explain the distribution of reputation and prestige in society.

Does reputation matter? Yes, but not how most of us would think. At a societal level, reputation plays a crucial and essential function in a moral community: people who commit immoral acts risk developing a bad reputation. This creates an incentive for people to avoid such acts. Meanwhile, at the individual level, people are obsessed with achieving a widespread good reputation for themselves. The problem is that, in our modern societies, this urge can become the source of many unnecessary wants and anxieties. It is only by overcoming certain aspects of our nature, including our fixation with social status, that we can master unpredictable interactions with the rest of our kind.