Can we really trust our emotions? The world seems full of people who end up tortured by their feelings. Can’t we just get rid of all that anger and sadness, all that guilt and envy, all that anxiety and delusional rage? Many ancient philosophies and religions aim to achieve this very goal through systems of control and repression, praising the benefits of having a non-emotional response to situations. But there are also very valid reasons for why we have the emotions we have, as the clinical psychiatrist Randolph M. Nesse points out in his book Good Reasons for Bad Feelings. It’s worth thinking about their implications for our well-being.

How we came to have our emotions

Nesse writes that “a stream of thought that goes back to philosophers in ancient Greece views emotions as maladaptive interlopers that undermine human reason. In Phaedrus, Plato viewed human lives as chariots pulled by two horses.” One horse is reason, the other is emotion, and each of them pulls us in a different direction. Even today, people still categorize decisions as either rational or emotional.

This view started changing when the philosopher David Hume argued in his Treatise of Human Nature that “reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.”

Hume had a particular interest for understanding how humans actually make decisions in their everyday lives. He came to the conclusion that our emotions provide the primary motivation for all our actions. Reason allows us to connect different ideas and form beliefs, which can in turn generate new emotions; but reason itself provides no impulse for action. This was the main insight of the Scottish Enlightenment philosophers, who accordingly inferred that our moral actions must have their root in innate moral feelings.

In many ways, modern psychiatry is a continuation of Hume’s project. Hume described his own enterprise as “an attempt to introduce the experimental method into moral subjects,” that is, to introduce the scientific method into the study of human nature.

Seen from an evolutionary perspective, our emotions evolved because they allowed us to deal with situations that arise in our natural environment. It might seem as if each emotion serves a specific function within a well-designed biological system, but that is not the case. What’s important to understand is that emotions mostly evolved to benefit our genes, not our subjective experience as individuals.

Our subjective experience of negative emotions can be distressing and disabling. Anxiety and low mood are often presumed to be problems in themselves, rather than symptoms. We have a tendency to ignore the effects of situations and attribute problems to the characteristics of individuals, something psychologists refer to as the fundamental attribution error.

The fact is that negative emotions can be very useful. Nesse points out that “anxiety and sadness are, like sweating and coughing, not rare changes that occur in few people at unpredictable times; they are consistent responses that occur in nearly everyone.” Such emotions are regulated by mechanisms that are turned on in specific situations. “The absence of a response can be harmful; inadequate fear of heights makes falls more likely. Some symptoms benefit an individual’s genes, despite substantial costs to the individual.”

The evolutionary process that shaped our species did not maximize the happiness of individuals; it only favored individual survival and reproduction. Anything goes as long as those two criteria are met. But how exactly did emotions benefit our genes in this evolutionary process?

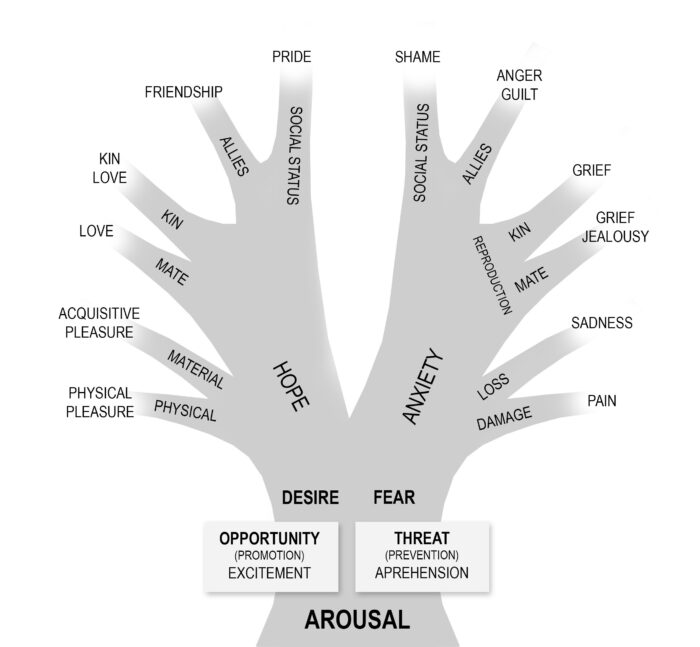

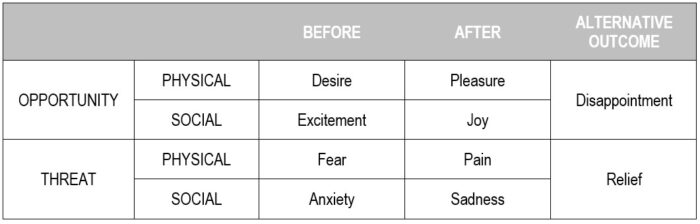

For Nesse, “emotions are either positive or negative because only situations with threats or opportunities influence fitness. Positive emotions encourage organisms to seek out and stay in situations that offer opportunities to do things that are good for their genes. Negative emotions motivate avoidance of and escape from situations that involve threat or loss.”

Our ancestors encountered situations in which emotions were useful: “falling, the sight of blood, a looming shadow, and sudden loud noises all indicate possible danger, so they connect to fear directly.” Fear is a rather primordial emotion, one that we share with many other species. However, what’s unique about us humans, unlike many other mammals, is the multitude of social emotions that we have.

Natural selection shaped us to care about what other people think about us. “This is what self-esteem is all about. We constantly monitor how much others value us. Low self-esteem is a signal to try harder to please others. However, trying to please others often conflicts with competing for status,” and this is what gives rise to the inner turmoil one often hears about in psychotherapy.

Sadness in general might seem useless: it comes “too late to do any good. The loss has already happened.” But sadness plays an important role in allowing us to cope with the situation of a loss. Feelings of grief promote a “rumination about what you could have done to prevent the loss,” which in turn helps prevent a repetition of the tragedy that happened. Sobbing signals a need for help, and creates a warning to others about the danger that afflicted the grieving individual.

As Nesse observes, we humans “make models of the world and project alternative futures across months and years. The outcomes of different possible actions play out in our minds. As we plan, fantasize, dream, and imagine, emotions nudge us toward some paths and away from others.”

But this leads to a challenge: “our strategies often involve complex social relationships and difficult decisions. Decisions about whether to give up on big projects that are failing are especially tough.” What roles do our emotions play in those crucial decisions, and how can we make sure they do not lead us astray? This brings us to the important role of emotional regulation.

How our emotions are regulated

Being a clinical psychiatrist, Nesse has witnessed all kinds of behaviors. “Some people worry for days about the meaning of a raised eyebrow that may have just been a twitch; others hardly notice direct insults. Some people are thrilled by small opportunities; others hardly shift in their chairs at a windfall. Both extremes have costs. People prone to intense emotions experience enthusiasms that shift their efforts from one unfinished project to another and demoralization that blinds them to new opportunities.”

He goes on to observe that “people who hardly experience emotion neither take full advantage of opportunities nor fully protect themselves against threats. Why such a wide range of responsiveness? A good guess is that people across the range have generally had similar Darwinian fitness.” This is in line with what the philosopher Daniel S. Milo pointed out in his book Good Enough: evolution does not always select a single optimal trait. Most of the time, it tolerates many seemingly “useless” traits as long as they do not significantly impact survival or reproductive success.

In our individual lives, “we all struggle to get relief from painful emotions. They are painful for a reason: to motivate efforts to change, escape, and avoid such situations. But changing or escaping a bad situation is not always possible. When it isn’t possible to help an addicted child or a dying spouse, useless terrible feelings arise. Even in everyday life, useless feelings plague us. Controlling them is an understandable goal.”

That is why we live in a world filled with self-help books, many of which suggest strategies for coping with and regulating our emotions. Most of these books “emphasize changing habits of thought or changing the meaning of the situation. Some try to dampen emotions directly by exercise, distraction, meditation, or psychotropic drugs.” The most effective strategy, however, is often to just wait, letting the situation change, letting the anger and emotional fog clear.

The reason for this is that our brains come hardwired with a psychological immune system. After experiencing extreme negative or positive emotional shocks, such as becoming a paraplegic or winning in the lottery, our “overall level of subjective well-being tends to revert toward the level before the accident or big win.” Although we might experience intense emotions in the short term, our minds tend to bring us back to a normal mood in the medium term, which helps most people bounce from disappointments much faster than they anticipated.

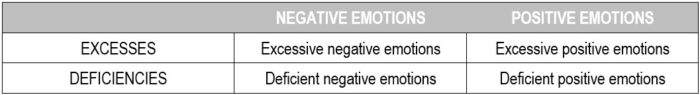

The problem is that some people are prone to emotional disorders. Nesse points out that there are two ways in which bodily responses can go wrong: “too little response or too much. People who never cough have a serious disorder, as do those who cough for no reason. Deficient immune response results in infection; excessive response causes inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.”

The same goes for emotions. Excess positive emotion is well illustrated by people prone to abnormal states of mania. “Some people in its grip are euphoric, but others are swept up in the uncontrollable pursuit of grandiose goals (…) Milder versions of unjustified positive emotion are great for those who experience them, but some perky people can be insufferable, while others blithely ignore social cues that make others wish they would be more sensitive.”

Negative emotions can also be deficient. “Hypophobia, insufficient anxiety, can be fatal,” while a “lack of sadness can result in doing the same stupid things over and over.” Nesse argues that “responses can be too quick, too slow, too enduring, or in response to the wrong cues. A quick temper is a problem, but so is a slow one or a tendency to hold grudges or taking offense for no reason. Anger can be useful if it is aroused by the right cues at the right rate to the right intensity for the right duration.”

Like Nesse, I also believe that anger has its uses, but I would go even further than he does in defending it. People with unexpressed frustrations often become prone to passive-aggressive behavior which only worsens the situation. If you are never angry, you are not Stoic, you are just fake and passive. Anger is nature’s way of giving you the motivation for standing up for yourself, for not letting others walk over you, for striking back. It is the prime driver of revenge, a form of ancestral justice. Without the deterrence of revenge, psychopaths would rule the world.

People react to anger with fear, and good leaders know that anger is a useful tool to shake things up when projects go wrong. Don’t just sit there like an idiot, do something! However, problems arise when anger turns into aggression, which modern systems of public justice cannot accommodate.

Emotions have meaning — a meaning that was shaped by hundreds of thousands of years of survival and reproduction in tribal societies. Nesse argues that “we should try to understand their messages. They are usually trying to get us to do or stop doing something. Sometimes they are wise and we should heed them. But not always. Sometimes they arise from our distorted view of the world. Sometimes they come from brain abnormalities.”

Our individual brains are prone to “historical and design constraints that make us all vulnerable to emotional problems […] Instead of assuming that positive emotion is good and negative emotion is bad,” we should rather “analyze the appropriateness of an emotion for the situation.”

We could easily question this line of thought. First, it’s easy to analyze a response in retrospect; but in the heat of the moment we always act first and think second.

Second, by what criteria can we judge the appropriateness of an emotional response? For many common situations (e.g. frustration at work or with your spouse), there seems to be a gray zone where it’s not exactly clear what response would have been the most appropriate; one might wonder if there is not a range of appropriate responses, depending on one’s values.

While it is difficult to judge responses in ordinary situations, things become perfectly clear when considering extremes. There is no doubt, for example, that it’s inappropriate to react to a suspicion of infidelity by killing your spouse and children and burning down the house. Likewise there is no doubt that it’s inappropriate to react to repeated abuse by doing nothing. So why do emotional deficiencies and excesses happen?

The origin of emotional disorders

Montaigne once wrote that “no one remains in a prolonged state of suffering except through his own fault.” This reflects a belief that he shared with classical Greek and Roman philosophers, namely that human beings are capable of resilience, allowing them to move on after going through emotionally difficult episodes in their lives; and that those who complain and linger in emotional suffering just exhibit a lack of mental self-control and agency. While that might be true for most of us, the assertion does not hold for those who suffer from emotional disorders.

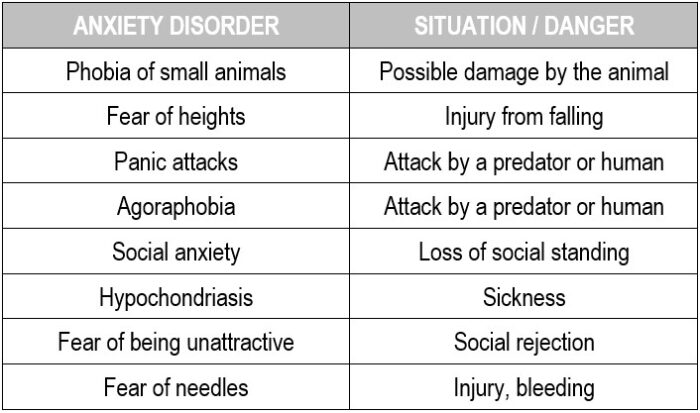

Nesse observes that “for people with anxiety disorders, mere hints of danger arouse sweating, tension, fast pulse, pounding heart, panicky feelings, and flight.” But why is anxiety so often excessive in some people?

We must first understand that anxiety is an emotion that evolved to safeguard us. “Systems that regulate protective responses such as vomiting and pain turn the response on whenever the benefits are greater than the costs, even if that means false alarms.”

Such systems follow the Smoke Detector Principle. In signal detection theory, “the correct decision depends on the ratio of signals to noise, the costs of a false alarm, and the costs and benefits of an alarm when the danger is actually present. In a city where car theft is common, a sensitive car alarm system is worthwhile despite the false alarms, but in a safer location it would be just a nuisance.”

Nesse notes that “a few fears are built-in automatic responses, but most common fears are not exactly innate. Fear of snakes, for instance, is not built in, but the brain is prewired to learn it fast.” Many fears are the result of “social learning of the most useful sort. Instead of a system that responds to only a few rigid cues, natural selection shaped a system that uses information from other individuals.”

This is why many fears are transmitted from generation to generation. “Parents who fear spiders, snakes or public restrooms can similarly transmit their fears to their children. We can learn to fear novel dangerous objects, such as electrical sockets, drugs, and knives, but such learning is slow because those cues have no prewired connection to fear.”

Most patients with a panic disorder experience anxiety attacks that “are false alarms in an otherwise useful system. These false alarms motivate more monitoring, causing increased arousal and increased system activity in a vicious cycle that makes further attacks more likely.”

What about depression? Several studies observed that “depressive episodes are precipitated by failure to accept a loss in a status competition,” where low mood emerges “as a normal response to losing a competition and depression as the result of continuing useless status striving.” In such cases, “many patients often recover when they give up an unwinnable status competition.”

Giving up a status competition is not as straightforward as it sounds. “Being in a subordinate position to someone with lesser abilities is a perilous situation. The natural inclination to show one’s stuff will be perceived as a threat, likely resulting in an attack or even expulsion from the group.” Many deal with this situation by “deceiving down,” that is, deceptively concealing their abilities. “After a status loss, signaling submission stops attacks by those with more power.” But in so doing they may end up convincing themselves that they are less worthy and able than they really are.

Nesse observes that “fighting an unwinnable status contest is one subtype of the more general situation of failing to make progress in the pursuit of any goal.” There are many other ways in which people can fail to achieve their desired goals, thereby triggering depressive episodes. In such cases, depression often motivates consideration for alternative strategies. In fact, “social withdrawal and thinking a lot can be useful when one encounters a dead end in life.”

On the other hand, “individuals whose mood rises in propitious situations can take full advantage of opportunities.” For instance, a “high mood creates a more expansive view of the world and a greater likelihood of taking new initiatives”, while “individuals whose mood goes down in unpropitious situations can avoid risks and wasted effort and can shift to different strategies or different goals. The capacity to vary mood with changes in propitiousness gives a selective advantage.”

As Nesse points outs, only three decisions are needed to maximize fitness in an evolutionary perspective. First, how much energy should you put into an effort, is it worth it? Second, when should you quit? Third, what should you do next? These questions remain extremely relevant in the modern world, and our mood plays an essential role in how we answer them.

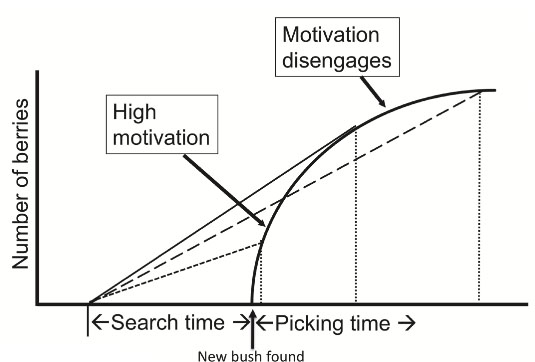

Let’s start with the first two questions, namely how much energy you should invest in a given endeavor and when to give up. Consider the scenario where you go out to pick berries in a field. “The longer you stay, the more berries you get from that bush, but to get to the most berries per hour, you need to stop and go looking for the next bush at just the right time. The best time to stop is at the point that gets you the most berries per hour,” as illustrated in the following graph:

In reality, there is no need to do any calculus to get to the right answer on when to give up picking on a bush. All you have to do is follow your emotions; they will tell you when to stop. You start enthusiastically, then gradually become more interested in moving to another bush. But some people don’t manage this. They just keep picking and picking on the same bush, even if there are almost no berries left. They have their own diagnosis: attention surplus disorder.

Making long-term decisions on career, health or spouse choices is relatively more complex than picking berries. Nesse correctly observes that in some professions, competition offers “huge payoffs for a few winners and years of useless efforts for everyone else.” More often than not, depression as a symptom arises “from a deep recognition that some major life project was never going to work.”

Low mood is not necessarily due to a disordered brain; it can be a normal response to pursuing an unrealistic goal:

She was glad he wanted to live with her, but it looks increasingly like he will never agree to get married. The boss is nice now and then hints at promotions, but nothing will ever come of it.

Nesse notes that “many people think that mood reflects what a person has. This is an illusion, as illustrated by the many rich, healthy, admired people who are nonetheless despondent. People strive to get things, expecting happiness, but it doesn’t work for long. Mood is only modestly influenced by what a person has and only briefly influenced by success or failure. Baseline mood is remarkably stable for most people, and variations reflect mainly the rate of progress toward a goal.”

The fact that low mood is linked to personal goals means that there is an inherently subjective factor involved. “Emotions don’t arise from events; they arise from a person’s appraisal of what events mean to his or her ability to reach personal goals.”

Low mood effectively disengages motivation and induces “waiting and considering alternative strategies; then, if no alternative seems viable, giving up on a goal. But is low motivation really the best response in such situations?” Wouldn’t it be better for people to take on a more positive view on life after a difficult event?

Nesse answers this question by first observing that “sometimes they do. Some people come home after losing a job and quickly realize they have been freed from what would have been decades of drudgery. After a divorce, initial despair is often followed by realizing that better relationships are possible.”

Yet “rose-colored glasses make optimists persist happily without the hesitation that plagues others. This can lead to the Concorde Effect, the mistake of continuing to sink effort into a hopeless cause.” It’s not easy to determine a completely objective cut-off point for all endeavors. “Usually it is better just to carry on despite problems,” but “at some point, carrying on is a mistake.” Some studies even show that low mood makes people more realistic, a phenomenon called depressive realism. Nesse points to other studies showing that people generally are unjustifiably optimistic.

When a major life crisis happens, “low mood dispels optimistic illusions and promotes objective consideration of alternatives.” This shift is often very painful. Nesse tells of patients in therapy “who thought that their marriages could recover, until a moment when suddenly all hope fell away, as if their rose-colored lenses had suddenly gone dark.” The costs and risks associated with some life decisions are very high, and pessimism can prove beneficial in avoiding hasty or naïve decisions.

What psychiatric research has demonstrated, however, is that some excessive emotional states are not only caused by circumstances or beliefs; they are strongly determined by our individual genetic inheritance.

The genetic lottery of personality

Real problems arise when our mood regulation system fails, as is the case with bipolar depression. A normal psyche “shifts mood higher and lower as situations change,” then returns the mood to the baseline, whereas “people with bipolar disorder have a broken moodostat. When they encounter a new opportunity, their mood goes up, but it does not come back down.”

Instead their energy, ambition, risk-taking and optimism increases in a spiral towards ever greater grandiose goals, until they reach “a manic excitement that can be fatal, simply from physiological exhaustion. Usually just before that point, some kind of overload switch turns motivation off suddenly and completely, resulting in a depression that feeds on itself.” Imagine how it is to be that person.

A striking fact is that who gets bipolar disorder is explained almost entirely by genetic variations; genetics explain 70% of the variation in vulnerability. If you have an identical twin with bipolar disorder, your chances of having it are 43 times higher than the average person on the street.

One would think that depression can therefore be traced down to some particular allele that carries the illness. But that is not the case! There seems to a bunch of different alleles which together form a complex and opaque web of causal antecedents for depression. “Disease risk is influenced by variations in thousands of genes with tiny effects interacting with one another and the environment.” Nobody has managed to figure it out yet.

Schizophrenia is another extreme personality disorder, and similarly to bipolar disorder it affects approximately 1% of populations worldwide. Each has milder forms affecting 2 to 5% of people. Genetic variations explain about 80% of the risk of having schizophrenia. Having a parent or a sibling with it increases your risk roughly tenfold. Its prevalence is remarkably consistent across cultures.

“Because identical twins do not always have the same diagnosis, some conclude that an environmental factor must also be involved. However, studies of adopted children show that the family in which a child is raised has little influence on the risk. It is more likely that the differences between identical twins result from chance variations influencing brain development, such as which genes are turned on or turned off and when, and the wandering paths of neurons as they grow.”

From an evolutionary perspective, Nesse observes that “people with schizophrenia or autism have far fewer offspring than unaffected siblings, with the reduction stronger for men than for women.” This implies that “selection against these disorders should be strong.” Yet they remain a remarkably persistent phenomenon.

Depression used to be referred to as melancholia, and we know that extreme moods have been present since ancient times. Recent research shows that the genetic variations that influence vulnerability to schizophrenia first appeared 5 million years ago, after our last common ancestor with the chimpanzees.

Nesse believes that the prevalence of these conditions is due to “the same genetic tendencies that make a disorder likely also give other advantages.” This is supported by genetic studies of Alzheimer’s disease. Humans developed alleles that enhance brain development at a young age. But the very same alleles “also increase the risk of late-life diseases” such as Alzheimer’s. This phenomenon, called antagonistic pleiotropy, “imposes much higher costs for organisms, such as humans, living in environments vastly different from those they evolved in.”

Studying people with disorders also reveals some interesting cues. For instance, “the likelihood of developing bipolar disorder is associated with higher-than-average levels of sociality and verbal skills,” which might be indicative that there are also benefits associated with their genetic makeup.

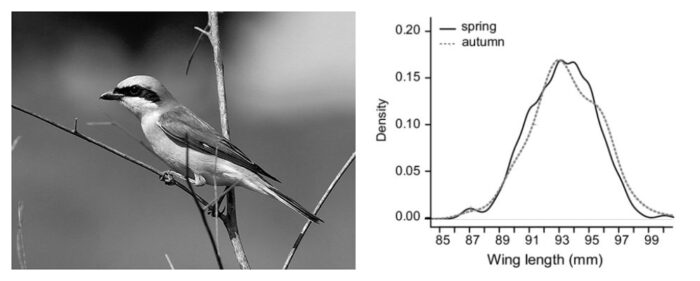

A fitness landscape provides a useful frame for thinking about how variations in a trait influence Darwinian fitness. “For instance, birds that have wings that are longer or shorter than average are less likely to survive a storm,” which is why observed wing length follows a bell curve, “with a fitness peak in the middle at the average length and smooth downward slopes on either side as fitness decreases for birds with shorter or longer wing span.”

Now consider racehorses, which “are prone to breaking the canon bone in their legs. Why didn’t natural selection make it thicker? It did; wild horses are unlikely to break their legs. However, breeding only the fastest horses made their leg bones longer and longer, thinner and thinner, and lighter and lighter. Successive generations of racehorses have become faster and faster but also more and more vulnerable to breaking a leg, something that now happens once every thousand times a racehorse starts a race.”

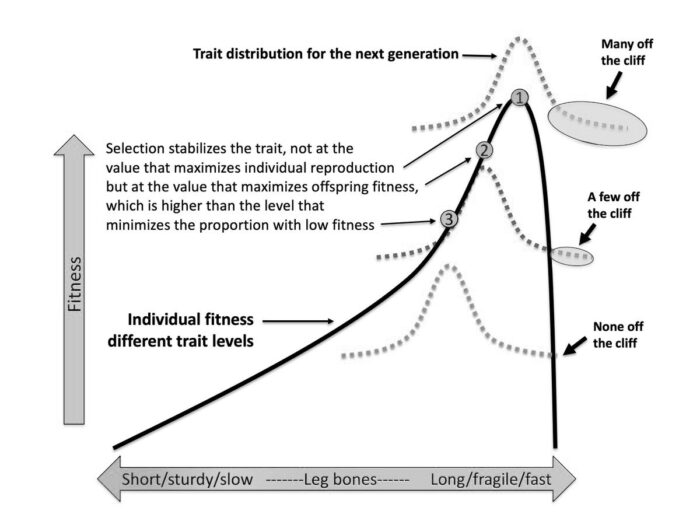

Racehorses have reached a point where further reducing the strength of their leg bones would exponentially increase their chance of breaking during a race. This could be called a fitness cliff. Fitness might increase when you push a trait in one direction, but at some point, “going one step too far results in going off the cliff.”

Nesse argues that “strong selection may have given us all minds like the legs of racehorses, fast but vulnerable to catastrophic failures. This model fits well with the idea that schizophrenia is intimately related to language and cognitive ability. It also fits well with the observation that schizophrenia may be intimately related to the human capacity for theory of mind, our ability to intuit other people’s motives.”

An individual at point 1 on the graph above “will have the maximum number of offspring, but inevitable variations among those offspring (the dotted curve above point 1) will leave many off the fitness cliff with a high vulnerability to disease.” Between one generation and the other, the apple can fall very far from the tree.

Many traits are subject to catastrophic failure. For humans, “babies with larger brains and heads have advantages, but in environments without obstetric surgery, just one centimeter too large is fatal for both mother and baby.” Likewise, immune system responses are very likely to have steep cliffs. As Nesse points out, the price of not being able to defend adequately against an infection is death. In order to ensure the ability to counter such threats, the immune system is shaped to an optimal level of aggressiveness, which if pushed further results in attacks against normal tissues and autoimmune disorders.

Nesse’s hypothesis is that mental disorders “may result from natural selection stabilizing traits at the point close to a cliff edge that maximizes genetic fitness despite the dire outcomes for a few individuals.” For him, “this offers a potential explanation for why we have been unable to find specific genetic causes for specific mental disorders,” even though much indicates that the conditions are inherited.

This evolutionary approach “forces an acknowledgement of diversity. There is no single normal genome, brain, or personality.” Variation is intrinsic to our genetic makeup, just as variation is also intrinsic to the circumstances we go through in life, resulting in subjective experiences that vary tremendously.

The importance of lived experience

When we experience an event that affects us, our emotional response will depend on the specific nature of the circumstances, the mechanisms in our brain that trigger our immediate emotional response and the beliefs that shape our interpretation of those circumstances.

The problem here is that our emotional response is not part of a conscious process; our immediate response to a situation is driven by complex unconscious mechanisms that are often in large part genetically determined.

We all have different minds, which also means that we have different abilities to follow well-intentioned advice. We do not necessarily choose how we react to the world; in many ways, our genes and our unique personal histories lead to fixed unconscious responses which may or may not be beneficial to us. This is the trouble we face with the human mind: the more we dig, the more we discover that our agency is more limited than we think. There is nothing we can do about factors that we cannot control. You either have lucky genes, or you do not.

However, it’s not all about genes. For instance, people who experienced adversity at a young age often seem to discount the perceived benefits of long-term commitments, preferring to take advantage of opportunities here and now. Researchers refer to this as “fast and slow life histories,” which “may explain the association of early adversity with borderline personality.”

The most extreme mental disorders only affect a small part of the population. Few of us carry disadvantageous genes, but most if not all of us will face some form of adversity in life. The sheer complexity and variety of idiosyncratic human lives makes it difficult to understand all causes explaining one’s state of mind, but there seems to be some useful general lessons to be drawn from Nesse’s experience of doing therapy with his clients:

People have dramatically different personalities. They create the situations they find themselves in. The situations they find themselves in further create the person. Very often those situations are self-stabilizing. People who are resentful and angry provoke anger in those around them, confirming their view of the world. People who see good in everyone often find it, sometimes because they have created it. But trying to shift an individual’s worldview is [pointless.] No amount of logic or argument helps much. What works is experiencing a kind of relationship that is different from all previous ones.

Many unconstructive beliefs are self-sustaining. “People capable of trust pair up with similar others and are likely to have relationships that confirm their positive expectations. They shy away from cynical types. People who think that others are self-interested tend to have untrusting and often untrustworthy associates who confirm their views.” One could describe this phenomenon as the ghettoization of beliefs, for lack of a better term.

People also go to considerable lengths to defend their worldviews. In therapy, Nesse frequently gets the “you are just doing it for the money” test; one patient even called him at midnight demanding that he come over to his house to help prevent a suicide, taking the challenge to another level.

He underlines that no amount of logic and argument will convince these people to change their mind. However, they might incur a reversal of belief if they go through an experience that conflicts with everything they had in mind. This points to the importance of living a life where we can learn from experience, where we expose our own beliefs to the test of reality, rather than a life of seclusion — where we may get stuck in a world of self-fulfilling prophecies.

Is there such a thing as a balanced emotional life? One could argue that, in the modern world, it is better to avoid useless feelings and extreme behaviors when possible. A sign that our emotions may not be trustworthy is perhaps to be found in their intensity and duration; when strong emotions persist for a long time, it might be good to pause and reflect on what is going on.

“Sometimes low mood should be respected as normal and useful to help adjust a person’s motivation and life directions. However, often the situation can’t be changed.” The world remains silent when we babble about existential questions; it remains silent when we complain and suffer in a corner. But it isn’t silent all the time. The world does answer you when you act. It gives you consequences.

I’m inclined to think that those who know how to expose themselves to, and infer the correct conclusions from, diverse experiences are more likely to be happy than others. In order to draw the correct conclusions, we must become aware of the role that both luck and personal beliefs play in our lives. We may be slaves to our passions, as Hume once argued, but our passions are also to some extent shaped by our individual experiences.